AGI isn't “coming” – it's already reshaping how young people think

Many thanks to Caitlin Krause for bringing her recent piece to my attention on the growing problem of young people forming emotional bonds with AI. She rightly highlights as a concern that AI companions are being designed to replace human connection, rather than augment it.

The risks she documents are real: isolation, emotional manipulation, and vulnerable people forming attachments to systems optimised for engagement rather than wellbeing. I think she's absolutely right to sound the alarm.

But I also think there's one more step to take.

Krause calls for “a new digital literacy” and for schools to teach young people about these risks. Things like emotional design, understanding boundaries, recognising manipulation. This is all very sensible. I'd also say, though, that it's insufficient. Not because the teaching would be bad, but because we're thinking about this problem as something schools will “solve” through better instruction.

The real problem is not pedagogical.

AGI is here now

I'm persuaded by Robin Sloan's argument that Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) isn't coming in five years; it's here now. It's now over five years since the emergence of GPT-3's few-shot learning capabilities. Treating AGI as perpetually something that's coming “in the future” serves the companies building these systems well: it allows them to defer accountability, design changes, and hard conversations about what these systems are actually optimised for.

Elon Musk wrote the rulebook around this. How long has Tesla been “a year away” from fully-autonomous vehicles?

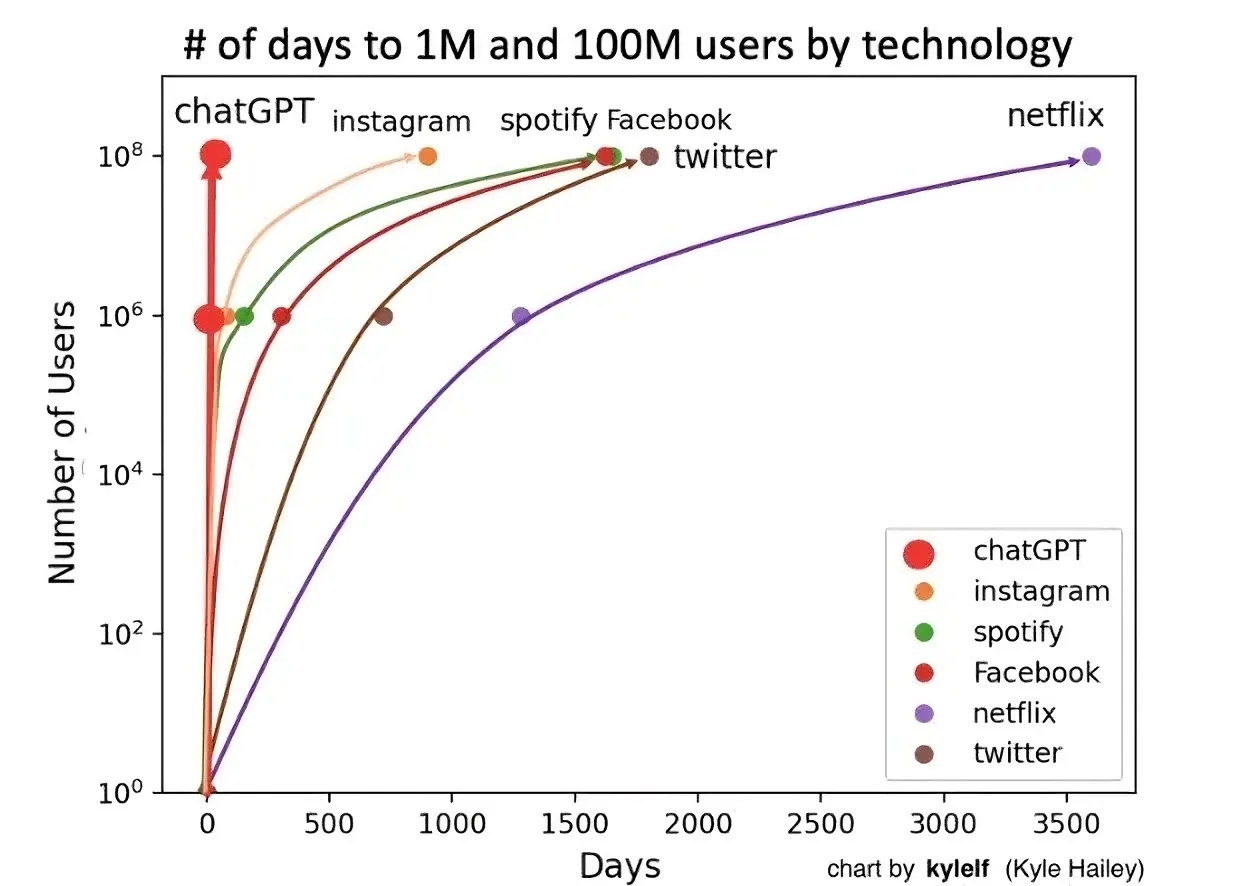

In the same way, we can't wait for perfect guidelines, for all teachers to be trained, or for consensus on what schools should teach around AI. Large Language Models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT are the most rapidly-adopted technology ever.

People are engaging with AI companions, forming attachments, and navigating these systems today. Literacies need developing now, in real contexts, alongside the technology itself.

Treating this as a “school problem” serves corporate interests. Deferral is profitable because it delays accountability. To understand why deferring literacies development doesn't work, we're going to need to rethink what literacies actually are.

Literacies are plural

Researchers have long argued against singular “literacy” frameworks. In my doctoral thesis I built on this work to argue that we should talk of digital literacies (plural): context-dependent, socially-negotiated practices that shift as technologies, cultures, and relationships change.

Helen Beetham has championed this approach for years, arguing that critical digital literacies are relational and situated practices rather than individual competencies to be acquired. Calling something “AI literacy” frames it as a skill everyone needs individually. This obscures something structural: that AI systems are built by specific people, funded by specific companies, and optimised for specific business models. They're not neutral tools requiring individual competency, but e deliberately designed environments that shape relationships and extract value.

So a literacies approach asks different questions. Instead of “What skills do students need?” we might ask “What capacities do people need to navigate a world where these systems exist?” Instead of “How do we teach about AI?” we ask “How do people develop, together, shared practices for engaging critically with these systems?”

My research proposed Eight Essential Elements for digital literacies. It's not a hierarchy or checklist; in fact, I often referred to it as an anti-framework. Instead, the elements that operate simultaneously across different contexts. They combine in interesting ways. Understanding AI's cultural meanings matters as much as critical evaluation. Confident agency (the ability to say no) matters as much as creative imagination about alternatives.

Angela Gunder at Opened Culture has remixed this into the Dimensions of AI Literacies, maintaining the plural, relational approach whilst applying it specifically to AI. We Are Open Co-op's approach to AI literacies builds on these foundations, helping people understand AI's impact in meaningful, practical ways.

The relational aspect is so important. Young people develop the capacity to recognise emotional design manipulation through conversations with trusted people, noticing patterns across their own experiences, and peer discussions about what they've observed. These are literacies developing through participation, not delivered through instruction.

What UK institutions are missing

The current landscape across UK schools, colleges, and universities shows activity and confusion. The Department for Education has published non-statutory guidance on AI. Most multi-academy trusts are in the process of developing policies.

The Gatsby Foundation's recent report on further education colleges shows growing interest in generative AI, but also real barriers: technical integration, GDPR concerns, budgets, and staff training needs. Jisc's work supports institutions in navigating this.

Universities have moved faster, driven by the reality that students can use language models to generate essays. Many now use a three-category system:

- AI use prohibited

- AI use allowed with acknowledgment

- AI use integral to the task.

The Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) has published resources in this area, and universities such as King's College London recognise that appropriate use varies by discipline.

What's absent, though, is a strong literacies framing. The guidance tends to focus on what Krause refers to as substitution: acceptable use, academic integrity, risk management. In other words, “Do this. Don't do that.” What's missing entirely is guidance on how students actually develop capacities for critical engagement.

What does a literacies-informed institution look like?

Instead of just teaching “AI literacy,” institutions need to ask: What conversations need to happen? Rather than shoehorning everything into a unit or module, thinking should be more strategic and holistic across programmes.

For example: Computer Science students could investigate how LLMs are trained and what that means for bias. English students might explore how AI affects writing and thinking. Philosophy students could engage with questions about agency and design.

Disciplinary questions become deeper when AI is present. When I studied Philosophy, the trolley problem was a thought experiment. Now we need philosophers and ethicists at tech companies as self-driving cars and robots meed to make autonomous decisions about the value of human lives in split seconds. These aren't abstract exercises any more.

The thing that develops literacies faster than any training programme is teachers and students investigating together, asking real questions about how these systems work in their discipline. I think that the assumption that staff need comprehensive understanding before engaging with students is a fool's errand: it just delays learning.

We also should be encouraging students to learn with their peers how to use AI – and then share practices they've developed with others. These conversations establish healthy norms and shape literacies much more than institutional policy does.

And families. They're already active participants in relationally shaping how systems work in their lives. Home is a really important site for the development of literacies. Institutions should be supporting rather than sidelining family conversations about boundaries, relationships, and observations. This isn't just for younger children, it's for young adults, too. After all (as I know) university students have a lot of holidays and spend plenty of time back on the ranch.

Literacies develop across multiple sites, not just in classrooms. Young people develop AI literacies through classroom discussions, but also family conversations, peer networks, and solo reflection. Institutions can create conditions for that development, but can't “deliver” it through policy alone. It's important for institutions have policies, but what they're lacking is the infrastructure for literacies development.

What needs to change

So what does that infrastructure look like in practice? This isn't only the responsibility of educational institutions, but they're a useful starting point.

Schools and colleges need to move from substitution to transformation. Before adding an “AI safety” unit, perhaps ask: How does AI show up across what we already teach? Even History, which I used to teach, can help students think about who builds systems and why. The key is teachers and students investigating together, asking real questions about how systems work in their context.

Families shouldn't wait for schools. They're probably already having to navigate managing screen time, conversations about appropriate relationships, and deciding which apps to allow. These conversations can be more focused. Parents help shape how young people understand the world around them. These conversations are where literacies develop.

Designers and builders should heed Krause's call for “speed bumps.” Friction can encourage reflection, and so should be designed in, not designed away. Systems should remind users they're talking to AI, suggest taking breaks, and be designed for agency, not to maximise engagement.

Policymakers understand that regulation matters, but policy alone won't build literacies. They need to support community-based approaches, and fund schools to investigate AI, not just comply with directives. It's also important to support parents navigating difficult decisions they may not have had to wrestle with before. That's where peer networks are useful to help share promisingpractices.

Universities should stop waiting for guidelines and start conversations immediately among staff and students. What does AI mean in your discipline? How do your students need to think about it? This is intellectual work, not compliance. Since assessment is central to higher education, it's a good idea to literacies development visible and valued in assessment feedback. Even summative assessment can be formative if done correctly.

None of the above requires waiting. All of it needs is to start where you are, in your context, with the people around you.

Why this matters right now

I'm glad Caitlin Krause raised the alarm about emotional AI. She's right to. The question is what happens next – how do we develop the capacities people need when AI systems are this sophisticated and pervasive.

As I've argued above, the answer isn't better school lessons, but the development of literacies across contexts, through socially-negotiated, context-dependent participation.

These systems are already shaping relationships and affecting how young people understand connection and agency. They're embedded in institutions and daily life. The literacies people need to engage with them can't be deferred to some future date when everything is figured out.

This is about treating young people as sensemakers rather than vessels to be filled. We need a literacies approach to AI where young people have agency, where relationships are negotiated thoughtfully, where people together figure out what it means to engage critically with these systems. Literacies develop through actual participation in the world, not instruction about it.

That begins where you are. In your classroom, your home, your community, your organisation. Not with waiting for better policy. With starting conversations and paying attention to what people actually need.