Why books are now luxury goods

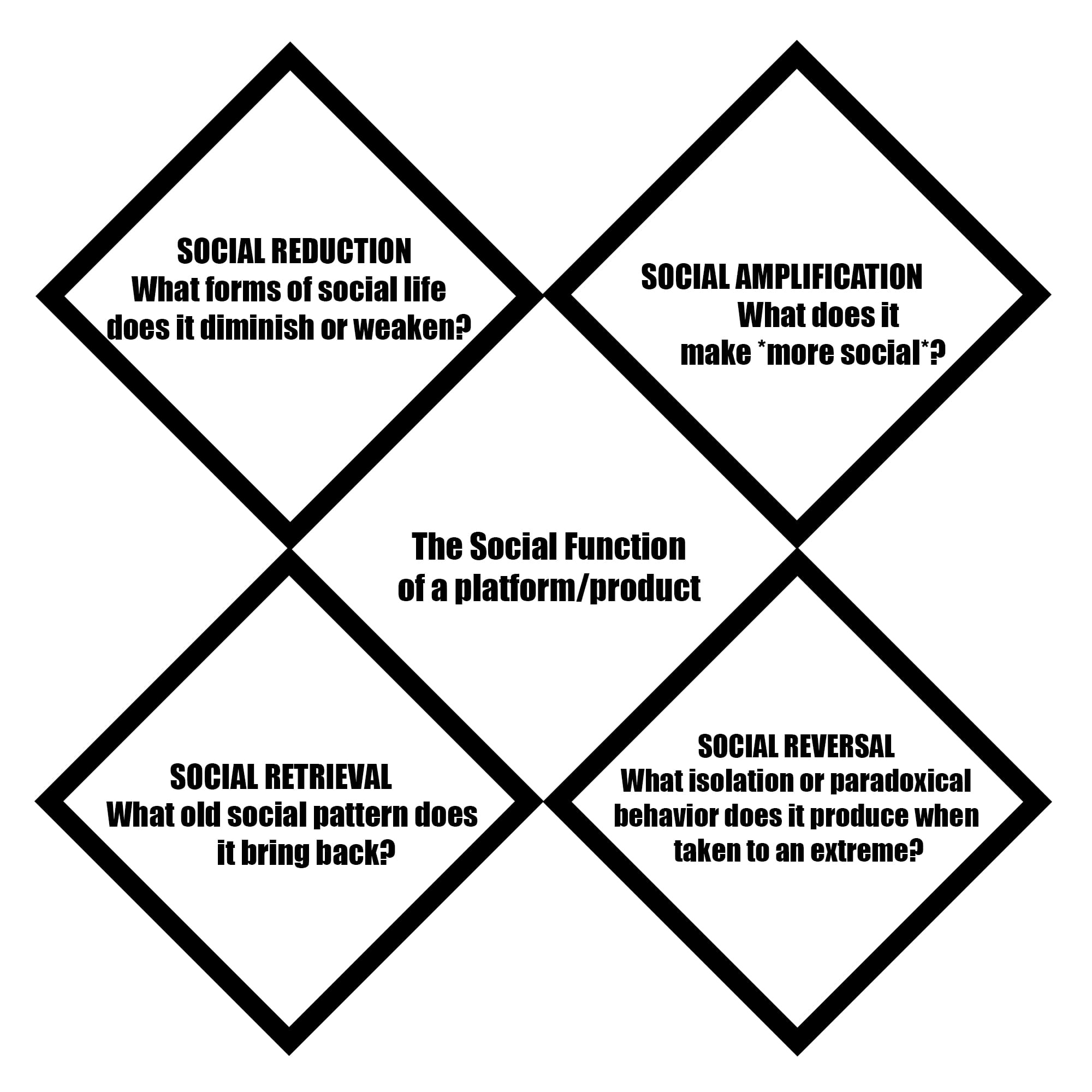

Marshall McLuhan's Tetrad of media effects is a touchstone in my world. It asks four questions:

- What does the medium enhance?

- What does the medium make obsolete?

- What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier?

- What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes?

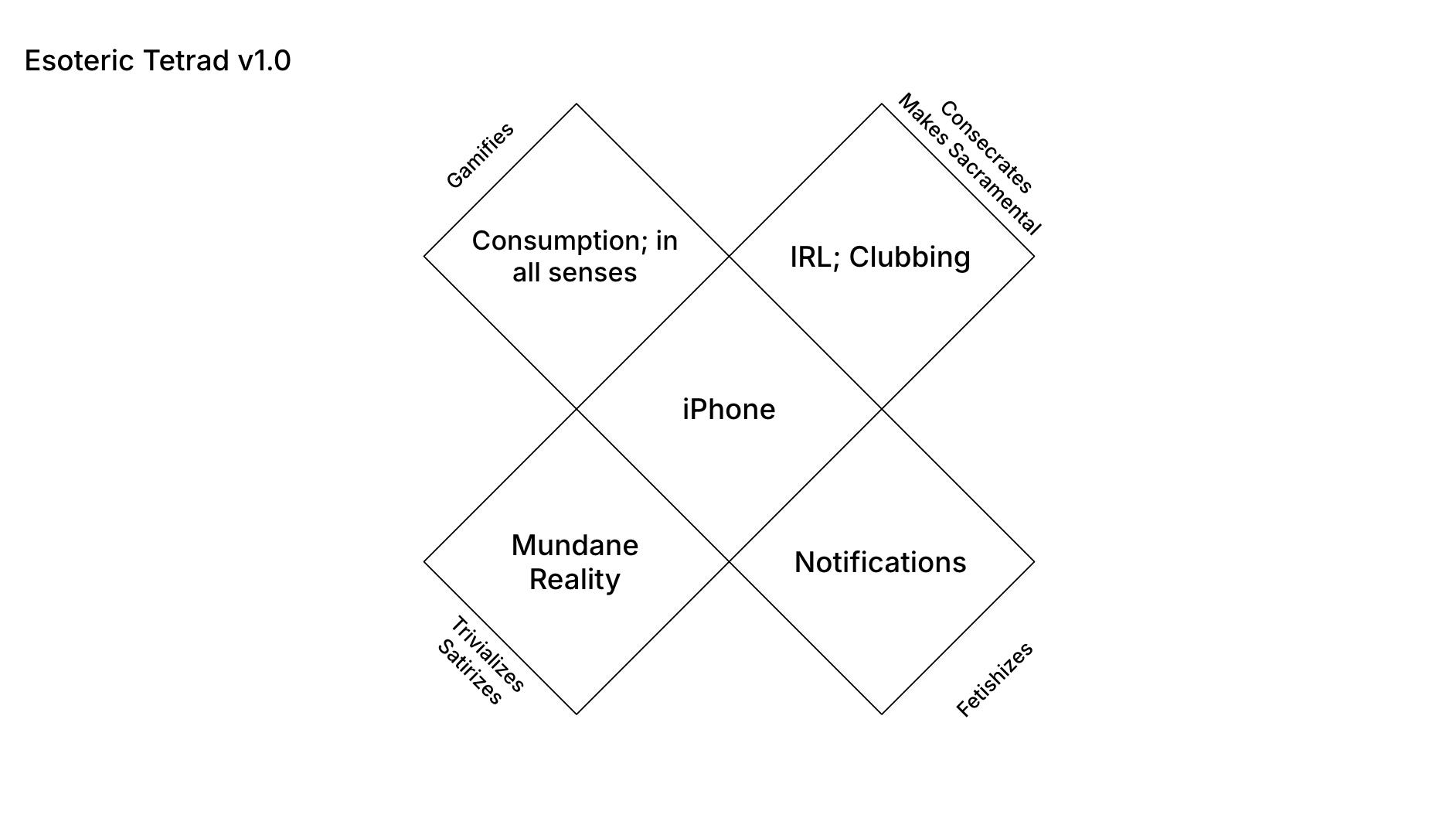

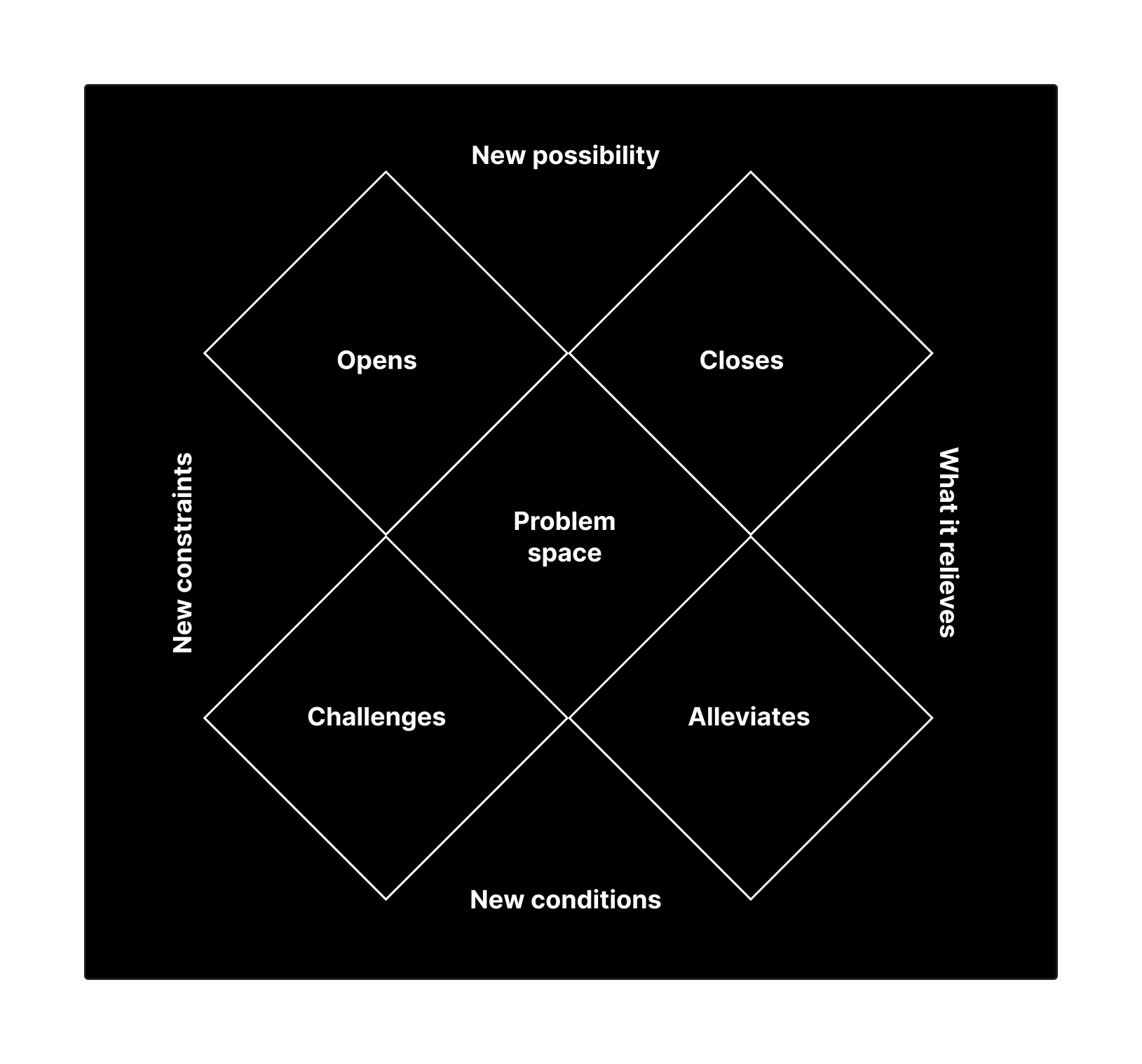

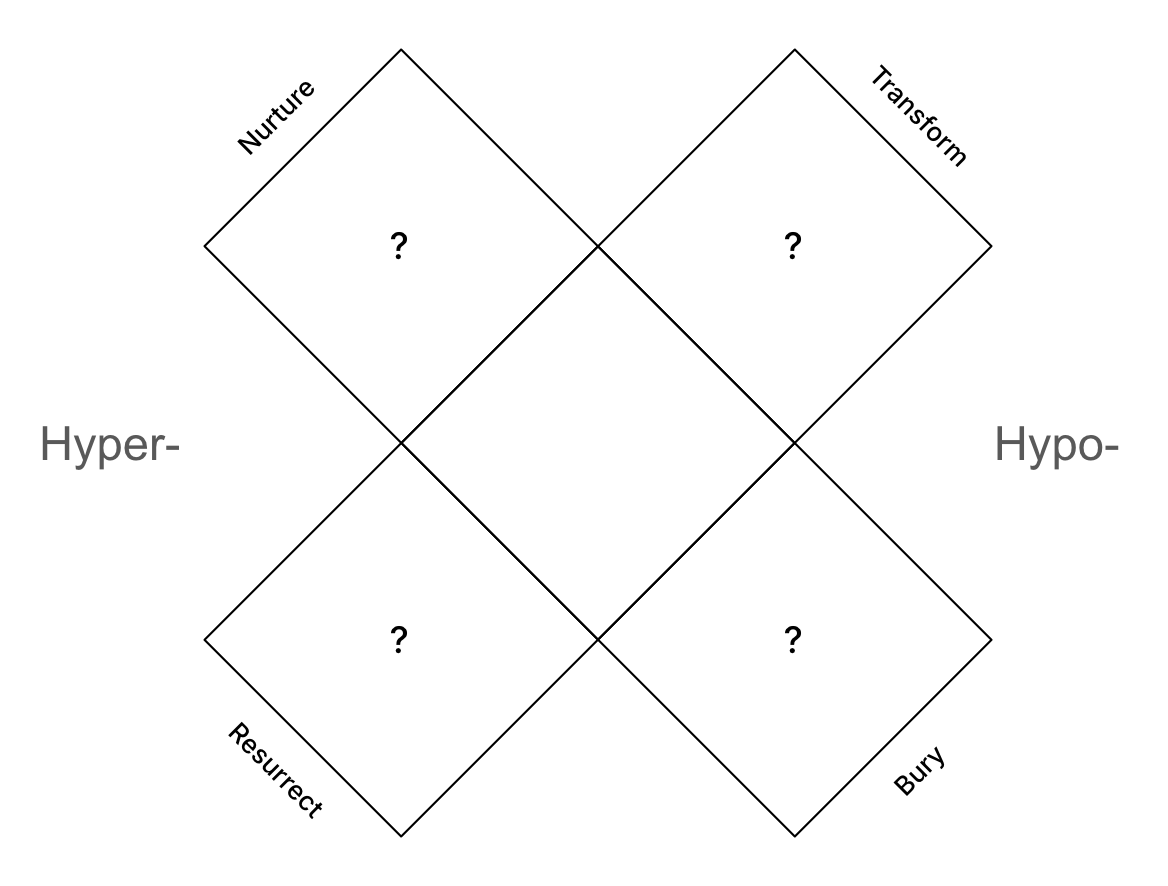

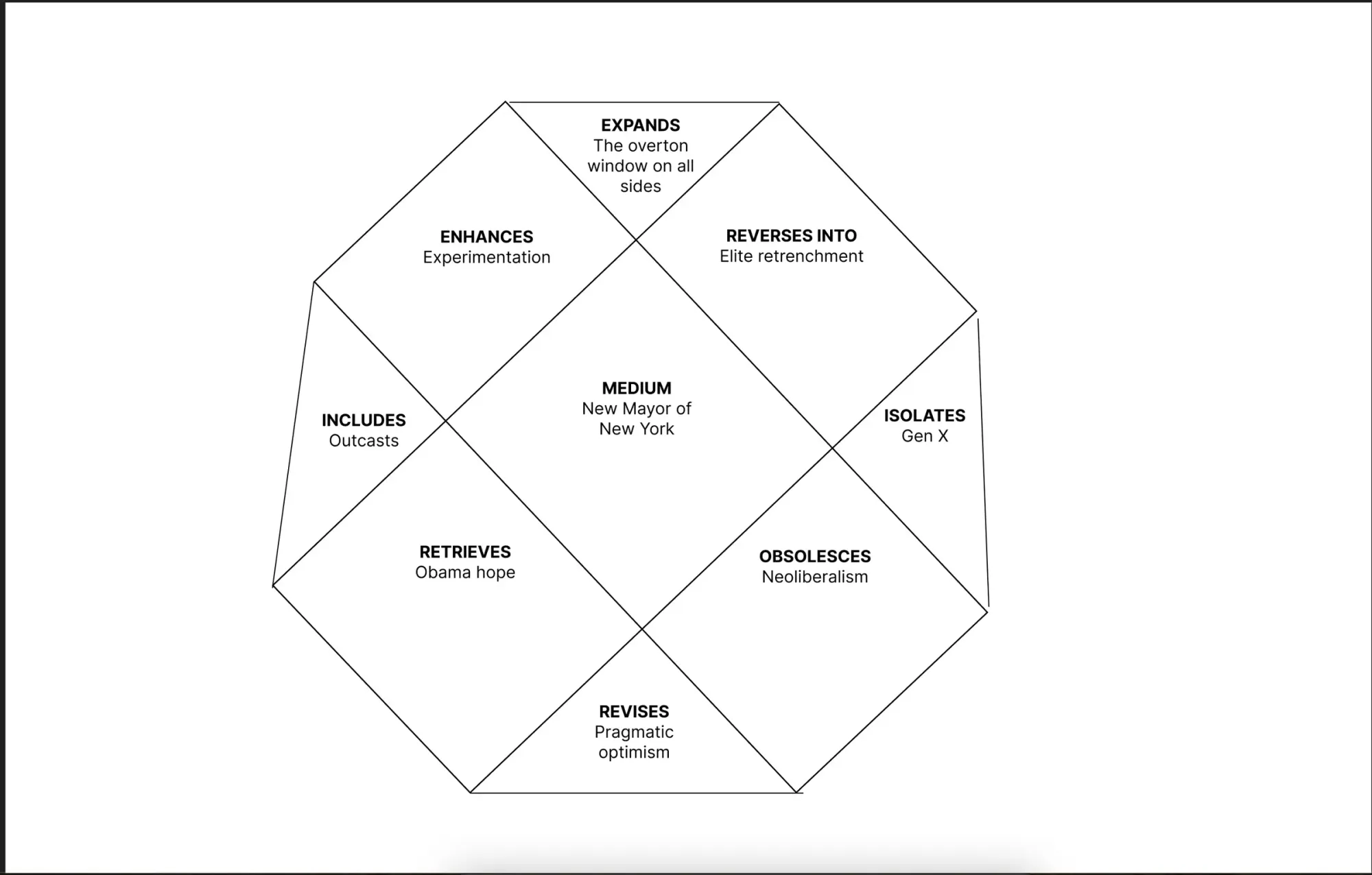

These days, though, tetrads can almost seem a “dead metaphor" (see ambiguiti.es), so I'm delighted to see these mutant tetrads from participants in a workshop run by Nemesis.

I find it interesting that Nemesis conceptualise an “anti-framework" in a similar way to me for the work I've done on the essential elements of digital literacies:

An anti-framework is a temporary, reflexive structure of process meant for noticing how frameworks constrain perception. It organizes thinking only long enough to expose the limits of organization itself.

For me, anti-frameworks open up spaces for cognitive play, allowing thoughts and assumptions to “slip out" almost unnoticed and spark ideas in others.

For example, I came across the Nemesis post via Warren Ellis, who had excerpted the following paragraph:

One of the most interesting parts of the tetrad is the quadrant regarding obsolescence because this is where you can find luxury as well. An easy example of this is how books are now obsolete as popular entertainment which makes them into valid luxury items for Miu Miu’s book club. The other most delicious part of of the tetrad (in our opinion) is the quandrant describing what the media object reverses into when pushed to its limit – which is also the trickiest part.

The above emphasis was added by me. Books as “valid luxury items”(!) Wow. But yes, obvious if you think about it. We are, in many ways, the other side of the Gutenberg Parenthesis and live in a world of what Walter Ong deemed “secondary orality."

I don't get demographic information along with the analytics for this blog, but I can almost guarantee if you've read as far as this paragraph then you're over 40 years of age. Most people younger than that (and many older than that) live in a world mediated almost entirely by images and videos.

This raises a question that the tetrad's third and fourth quadrants, obsolescence and reversal, are particularly good at helping us ask.

Media as luxury

The idea of books as luxury items fits a larger pattern of what happens when media shift from mass entertainment to niche status markers. Research on luxury goods signalling shows that wealthy consumers actively seeking status use “loud luxury” as a signal to the less affluent. Those less in need for such status instead pay a premium for “quiet goods only they can recognize,” Books, especially certain editions, imprints, or curated lists, function as precisely this kind of quiet luxury. They signal cultural capital that only fellow insiders can decode.

This pattern extends beyond books, of course. When a medium becomes obsolete as popular entertainment, it often becomes available as a luxury good for those who can afford the time, attention, and space to engage with it deeply. As Brian Eno noted:

Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit - all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.

We're seeing this with vinyl records, but also film photography, hand-written letters, and certain forms of slow, deliberate reading. All of these have been functionally replaced by more efficient digital alternatives, yet each in some way a distinctive marker which says someone who decides to consciously revel in the obsolescence.

We can think of media obsolescence in at least three ways:

- Functional obsolescence – replaced by superior technology

- Demographic obsolescence – abandoned by younger users

- Status obsolescence – abandoned by the masses, reclaimed by elites

Books fit the third category. I remember seeing a social media post in which someone found themselves at a retreat for wealthy individuals. They mentioned “everyone is carrying a book around with them” with the assumption that rich people reading is what explains their financial success. More likely, of course, is that it's exactly the kind of quiet luxury mentioned earlier.

Email arguably fits the second category – demographically obsolete, still used professionally but increasingly ignored by younger people who prefer messaging apps. The tetrad's obsolescence quadrant, then, isn't just about what disappears; it's about what becomes available for new forms of value creation.

(This has direct consequences for digital literacies. When a medium moves from mass to luxury, the competencies required to use it well shift from baseline skills to specialised expertise. That's a point worth returning to later.)

Interestingly, Gen Z is complicating this pattern. Their definition of luxury is “no longer tied to exclusivity or materialism alone but increasingly to individuality, emotional value, and responsible consumption.” Might the luxury-obsolescence paradox itself be becoming obsolete – perhaps replaced by a more fluid sense of what counts as valuable engagement?

While books and vinyl become luxury items, the platforms that displaced them are undergoing their own tetradic transformations. The trickiest transformations occur in that fourth quadrant: reversal.

Putting the tetrad to work

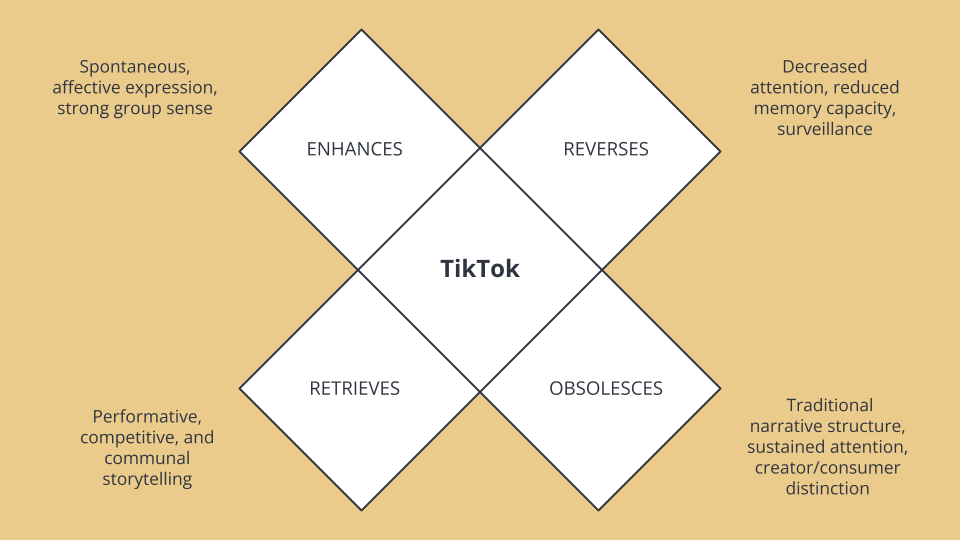

The Nemesis blog post discussed at the top of this post described the reversal quadrant as “the trickiest part.” I'd agree, but it's tricky partly because we rarely see the other three quadrants worked through with contemporary platforms. Let me try it with TikTok, which is not a platform I actually use. So this is in no way a definitive analysis, but rather as a way of making the framework do something.

ENHANCES – TikTok amplifies spontaneous, affective expression and creates what Walter Ong called a “strong group sense” through shared sounds, memes, and challenges. It amplifies what researchers call the frictionless flow of behavioural surplus (i.e. both content and users compete for ephemeral visibility in an attention economy)

OBSOLESCES – There is no narrative structure on TikTok, nor need for sustained attention on one thing. There is little distinction between creator and consumer, and in doing all this it also obsolesces older social media's reliance on text-based communication and notions of “following,” replacing these with algorithmic discovery and audio-visual stimulation.

RETRIEVES – Ong talked about pre-literate oral culture having an “agonistic style,” by which he means performative, competitive, and communal storytelling. TikTok retrieves this, along with the television-era experience of passive consumption, despite a veneer of interactivity.

REVERSES – When pushed to extremes (i.e. through excessive use), TikTok, which is designed for endless, frictionless entertainment reverses into what researchers call digital dementia. They characterise this as decreased attention, reduced memory capacity, and altered brain structure. It also reverses into surveillance, as the same algorithm that delivers pleasure extracts behavioural data, meaning that users are simultaneously performers and products.

This shows how useful the tetradic approach can be, but also reveals its limitations. The four-quadrant structure is almost too neat. It struggles to capture things that didn't exist in McLuhan's time: algorithmic feedback loops, data extraction, and the way platforms are a hybrid of multiple media forms.

That's where mutant tetrads become necessary, not as a rejection of the framework, but as an extension of it.

Um, so what does secondary orality reverse into?

McLuhan's belief was that media overheat, or reverse into an opposing form, when taken to an extreme. If we are, in fact, living in an era of “secondary orality,” what does that reversal look like?

One answer comes from Bonnie Stewart's work on academic Twitter. She shows that the promise of spontaneous, oral-style conversation is in tension with its persistent, searchable, and recontextualisable nature. The result is what researchers call “secondary literacy,” a condition where text-based interaction registers as having the immediacy of oral exchange, but without literacy's capacity for reflectiveness or the ability to develop a particular topic in any extended way. This helps explains something about call-out culture: the same features that enable rapid, affective connection also enable rapid, affective punishment.

Another reversal is cognitive: media designed to help us access, connect, and amplify information, when used intensively, are associated with the “digital dementia” mentioned above. In other words, the same platforms that create Ong's “strong group sense” can, when pushed to extremes, reverse into fragmentation, shallow processing, and what younger users (including my kids) brain rot. It's a little ironic that the medium that amplifies social connection reverses into cognitive isolation.

A third reversal relates to learning. The video deficit effect shows that children can learn from screens – but then often fail to transfer that learning to the physical world. For example, recent research found that infants learning from touchscreens only transferred their learning to other touchscreens and not to real objects.

These three reversals suggest that secondary orality, when pushed to extremes, doesn't simply return to “primary” orality or advance into some form of “tertiary” literacy. Instead, it becomes something... a bit strange: a hybrid that retrieves orality's ephemerality and agonism whilst, at the same time obsolescing literacy's depth and reflectiveness.

This is where mutant tetrads become necessary, not to replace the tetrad but to keep it from becoming what I term a “dead metaphor” – i.e. something that no longer has any explanatory power. An anti-framework approach, is precisely what's needed here. Using the tetrad to examine its own limitations is how we keep frameworks alive rather than allowing them to ossify into dogma.

What comes next?

So what does all this mean in practice? It explains why the generational divide in media consumption isn't just about preferences, but about inhabiting different cognitive regimes. There are different affordances, vulnerabilities, and luxury goods involved here.

The over-40 crowd (including me) still operates partly within the Gutenberg Parenthesis, where sustained textual engagement is a baseline skill. Meanwhile, the under-40s increasingly operate in a post-parenthetical environment where that same skill is becoming a luxury item.

This has direct implications for digital literacies. If secondary orality is the dominant regime, then I need to update my work to account for its specific demands: things like critical visual literacy, awareness of algorithmic curation, and an understanding of affective contagion in oral-style networks.

The competencies that matter are no longer just about reading, writing, and participating in literate communities. They now also include such things as recognising when a medium that amplifies connection is reversing into surveillance, or when a platform that retrieves community is obsolescing privacy.

It's a strange new world, and we need temporary structures to help understand it. For me, the tetrad's value isn't in its four neat boxes, but in its ability to keep us asking: What is this medium amplifying? What is it making obsolete? What is it retrieving? And, most importantly, what is it reversing into when we push it too far?

The answer to that last question, I predict, will determine what kinds of literacies we need next.