How to be less wrong in a polycrisis

I've already written about outdated mental models, about the pragmatic test of “cash value,” and about mental models better suited to 2026. This post is about an approach that makes those ideas workable: epistemic humility.

The fragility of what we know

Epistemic humility goes back further than Kant and Hume – all the way back, in fact, to Plato's Apology. It's a simple idea: our knowledge is always provisional and incomplete, and therefore might require revision in light of new evidence.

Epistemic humility emerges from our recognition of just how fragile our confidence is in the truth of any statement. According to Ian James Kidd, we decide on the veracity of something by considering three different conditions:

- Cognitive: specialised knowledge we may have in a particular domain

- Practical: our ability to perform certain actions which are required to prove the claim

- Material: access to particular objects we may have about which truth claims are made

These three conditions are context-dependent. That means what we “knew” to be true in one context may not hold in another. This is where cognitive biases come in.

Becoming bias-aware

Talk of cognitive bias often sounds like an accusation – as if some people are biased and others are somehow “objective.” In reality, bias is inevitable when our finite human brains try to cope with a complex, fast-changing world. Our evolutionary hardware just wasn't designed for it.

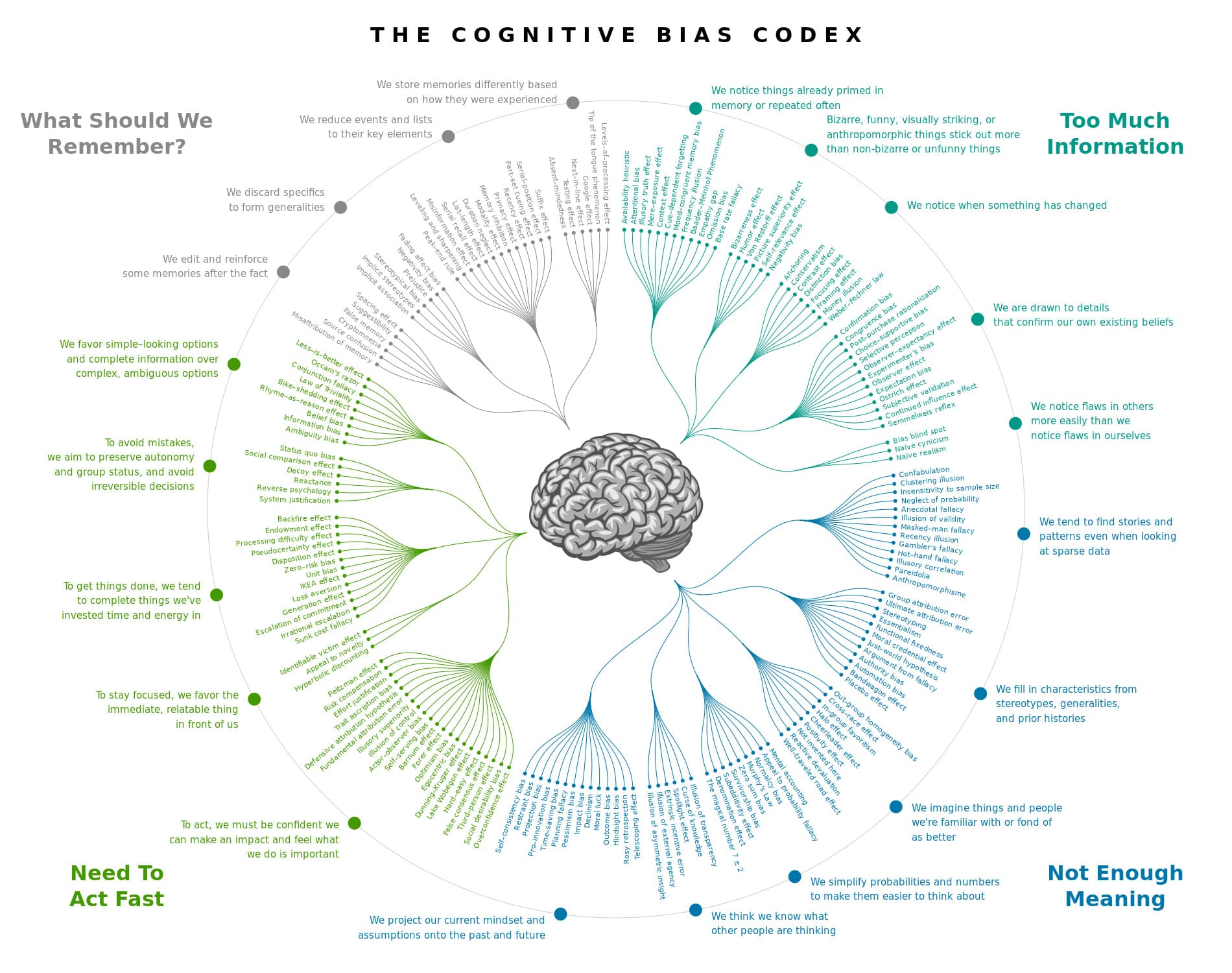

Buster Benson's cognitive bias codex (which I have hanging on the wall of my office) organises 200+ named biases around four problems:

Information overload sucks, so we aggressively filter.

Lack of meaning is confusing, so we fill in the gaps.

Need to act fast lest we lose our chance, so we jump to conclusions.

This isn't getting easier, so we try to remember the important bits.

These biases are not malfunctions, but strategies that mostly work. The trouble is that the same shortcuts that helped our ancestors survive can cause serious problems in the rolling polycrisis we're experiencing in 2026.

Confirmation bias means people notice examples that support their existing beliefs and discount evidence which contradicts them. For example, if you believe hard work always pays off, you will remember the successes and explain away failures as “exceptions.” Likewise, hindsight bias leads to successful people rewriting their own histories, treating luck and timing as if they were inevitable products of the wise choices they made.

Our goal isn't to become unbiased (whatever that means) but rather to become bias-aware in a way that makes our built-in quirks less harmful. This approach is one of epistemic humility.

Humility is not a personality trait

Humility often gets confused with traits such as low self-esteem or indecisiveness. But epistemic humility is not about “apologising for existing.” Instead, it's about taking seriously the gap between how certain you feel and how much you actually know.

Erik Angner writing in the early days of the pandemic, described epistemic humility as an intellectual virtue, offering some practical advice:

If you want to reduce overconfidence in yourself or others, just ask: What are the reasons to think this claim may be mistaken? Under what conditions would this be wrong? Such questions are difficult, because we are much more used to searching for reasons we are right. But thinking through the ways in which we can fail helps reduce overconfidence and promotes epistemic humility.

This is humility as a practice, rather than as a personality trait. It involves deliberately looking for ways you might be wrong. It means treating your beliefs as working hypotheses.

This article suggests it's an approach worth pursuing:

Epistemically humble individuals demonstrate superior discrimination between true and false claims, better calibration of confidence, and reduced overclaiming.

In other words, people who practise humility are, on average, better at telling when they might be wrong. They are more careful when they should be careful and more confident when they have good grounds to be.

Testing beliefs in practice

Ever since my undergraduate degree in Philosophy, I've described myself as a Pragmatist. Thinkers such as Charles Sanders Peirce and William James offer a way out of endless metaphysical debates about truth. Peirce, for example, suggested that truth is not a possession you either “have” or “lack” but a direction of travel. By repeatedly testing and correcting them, our beliefs can get closer to what works reliably in the world.

James, as was typical for him, asked a blunter question:

What, in short, is the truth's cash-value in experiential terms?

He goes on to say that true ideas are those that we can validate and verify in practice. False ideas are those that we cannot.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes Pragmatism as “knowing the world as inseparable from agency within it.” This is not relativism, but recognising that beliefs are tools, and tools can become obsolete.

So this is where epistemic humility and Pragmatism align: humility helps us say “my beliefs might be wrong,” while pragmatism asks “do my beliefs still have cash value in the current conditions?”

We need both humility and action. Humility without action can turn into anxiety, while action without humility becomes arrogance. Pragmatism offers a rhythm many of us could use: form beliefs, act on them, watch what happens, then change your mind if the results are not what you wanted.

Cultivating bias-aware habits

So what does this look like in practice? Here are three simple habits that combine epistemic humility, bias awareness, and Pragmatism.

1. Name the story you are telling yourself

Our brains are pattern-making machines. This means that, faced with incomplete information, we reach for stories. Cognitive biases like the narrative fallacy and hindsight bias are at work in these stories, helping them feel neat, flattering, and somehow inevitable.

Adding some epistemic humility to this simply involves naming the story:

- “I am telling myself the story that if I do not own a house by the time I'm 30, I've failed in life.”

- “I am telling myself the story that my lack of progress with my business is entirely my fault.”

- “I am telling myself the story that this career path is 'safe' because it was for my parents' generation.”

Once you name the story, you can test whether it's useful (“cash value”):

- Does this story actually help me make better decisions today?

- What results does it produce in how I spend my time, money, and attention?

- If I adopted a different story, what might change?

This is not about manifesting a nicer narrative. Rather, it's about admitting that you are always already telling a story, so you might as well choose one that aligns with current conditions. The test is simple: does this story still have cash value?

2. Ask yourself questions

Erik Angner, quoted above suggests two questions to reduce overconfidence:

What are the reasons to think this claim may be mistaken? Under what conditions would this be wrong?

You can use these two questions to test any belief you care about. For example:

- “University is always a good investment”

- “AI will definitely wipe out my job”

- “I am just not the sort of person who can do X”

Write the belief down and then underneath each, list:

- Evidence that supports it

- Evidence that could count against it (even if you have not seen it yet)

- Things that would change your mind

This is a small, practical form of epistemic humility. It's not about saying “my belief is wrong,” but rather “here is how it could be wrong, and here is what would make me update.”

3. Run small experiments

The Pragmatic approach is to treat beliefs as hypotheses about how the world works, then test them. That means treating each tactic as a hypothesis; trying it in the smallest possible way that provides useful feedback; keeping the ones that work, while discarding the rest.

My blog posts on various topics are a form of this. It's obvious from my analytics and what gets shared on social media the kind of things that people are interested in.

Some other practical examples:

- Before I started on my postgraduate degree in Systems Thinking, I took a one-day course to test my interest, and whether that institution was the right one for me.

- I advise anyone thinking about going into consultancy from a full-time job to first try reducing their hours and building a side project.

- Over the years, my wife and I have rented in a couple of places before we've bought a house to see what it's like in practice (how does it feel?)

Each experiment is a way of asking reality: does this belief have cash value, here and now? The answers might not be what you want or expected, but they are a form of action, and are usually more useful than abstract speculation.

Final words

We are living through what some call a polycrisis, where multiple crises interact in such a way that the overall impact exceeds the sum of each of the parts. The impact of climate change, AI, geopolitics, and changes around demographics shifts the ground beneath our feet.

As a result, it's no surprise that our old mental models are failing. While epistemic humility will not lower your rent, abolish your student debt, or find you a marriage partner, what it might do is help with three things:

- Reduce self-blame – it helps to recognise that some struggles come from broken maps and changing terrain, not personal defects

- Improve decision-making – by holding our beliefs lightly enough that we can learn from experience

- Prepare for systems change – shifting mental models is a prerequisite to achieving sorely-needed systems change

I've struggled with all of this myself, and I suspect I'm not alone. We can't sit on the sidelines forever, shrugging and saying who knows? Instead, we have to commit lightly by acting on the best models we currently have, while holding them loosely enough they can be changed when reality pushes back.

The world is a confusing place. Although the temptation is to seek certainty, the best approach is to become a little less certain, a little more curious, and a lot more willing to revise our judgements.

This is part of a series on updating our mental models in a polycrisis. In the next post, I will look at what happens when we remember that our minds do not end at our skulls – and how tools, environments, and recognition systems can make bias-aware thinking easier instead of harder.