Building a 'thinking system' to help you be less wrong

This is the second post in a series on updating our mental models in a polycrisis. In the first post, I argued for taking the approach of epistemic humility. It allows us to recognise that our knowledge is provisional, our biases are real, and our beliefs need regular testing against current conditions. This post is about what that looks like in practice when we remember thinking does not happen only inside our heads.

Recently, I moved my consultancy business from Google to Proton. What stuck with me after migrating between email and calendar providers were not just questions about where data lives. I realised that I was redesigning part of my thinking system.

Tools I use to send email, make notes, bookmark things, and keep track of events and tasks are all “cognitive prosthetics.” They help shape what I notice, what I remember, what I can do, and how I make decisions. In other words, they’re not neutral utilities, they’re part of how I think.

Philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers called this the extended mind thesis. In a paper published in 1998, just before I studied Philosophy as an undergraduate, they argued that:

Objects within the environment function as a part of the mind. The separation between the mind, the body, and the environment is an unprincipled distinction.

They are not saying, for example, that your smartphone is your brain. They are saying that minds work as “coupled systems” – that we should think of the combination of notebook, calendar, and brain as one system. After all, when a tool becomes reliably integrated into how you think, it is part of your cognitive process.

In my previous post in this series, I talked about epistemic humility – the idea that knowledge is always provisional and incomplete, and therefore might require revision in light of new evidence. If your thinking system is badly designed, the tools themselves can amplify the very biases you are trying to counter.

Tools shape what we see

As a concrete example, I recently started using Anytype for personal knowledge management. It uses a local-first, encrypted approach and lets me build exactly the structure I need rather than forcing me into someone else's template.

Using Claude Code as a thought partner, I considered carefully the approach I wanted and how to set it up. This resulted in a kanban-style approach with different levels that I've been longing for in other apps. You can see it documented it in this walkthrough.

I love how Anytype can show relations between ideas rather than only hierarchies. Objects can be tagged and linked in multiple ways, and the system grows organically rather than being one I have to maintain.

Research on cognitive scaffolding shows that how our external tools are structured influences our inner mental processes. When a tool makes certain operations easy and others hard, it nudges you towards particular ways of thinking.

Cognitive scaffolding is defined as external structures that “support cognitive processes by temporarily reducing task demands, enabling learners to focus on aspects of the task that are most relevant to learning.”

Although I do use some hierarchical elements in my project folders, regular collaborators know I'm more of a fan of searching and tagging. Otherwise, I can find it hard to see connections across categories. A relational database, such as the one underpinning Anytype, rewards linking and makes it easier to spot patterns.

Neither the hierarchical approach nor the search-and-tag approach is neutral; both are scaffolds that either support or hinder certain kinds of thought. Good scaffolding helps you think better now without creating dependency. Bad scaffolding, on the other hand, makes things feel easier while quietly atrophying your ability to think without it.

When tools amplify bias

As you can imagine, the extended mind thesis has a darker side. If tools extend cognition, they can also extend bias. Automation bias is the tendency to over-rely on automated systems and under-question their outputs.

A 2024 study on AI and anchoring found that people trust AI recommendations for “objective” tasks like stock predictions, but show “algorithm aversion” for subjective judgements like employee performance. Interestingly, this split is mediated entirely by user trust. When trust is high, anchoring is stronger. When trust is low, people ignore the AI entirely.

This isn't just an AI problem, however. Any tool that delivers information in a particular order or format introduces anchoring effects. For example: email inboxes reward recency. news feeds reward emotions like outrage; dashboards reward whatever metric is largest or feels most relevant; calendar notifications reward short-term urgency over long-term priorities.

When we are juggling multiple tasks, we rely more heavily on heuristics (mental shortcuts) and are less able to engage in deliberative thinking. The design of your tool stack either reduces your cognitive load or adds to it.

My current thinking stack

I'm not perfect, but simply working out loud to provide examples and to request feedback. Here is my setup, as of February 2026. It's always in a state of flux because I'm intentional about my tooling.

1. Anytype for knowledge management

I switched to Anytype because I wanted a European-based, flexible approach to projects under my control. But the real benefit is its relational structure. Instead of files in folders, everything is an object with properties and relations.

To me, this reduces confirmation bias by making it easier to see counter-examples. If I tag a note with “evidence against X” as well as “evidence for X,” those tags surface both when I search. Folder-based systems hide things you file away.

It also supports what I wrote about in my first post: treating beliefs as hypotheses. A belief in Anytype can have properties like “confidence level,” “last updated,” “evidence for,” "evidence against,” etc.

2. Proton for email, calendar, and files

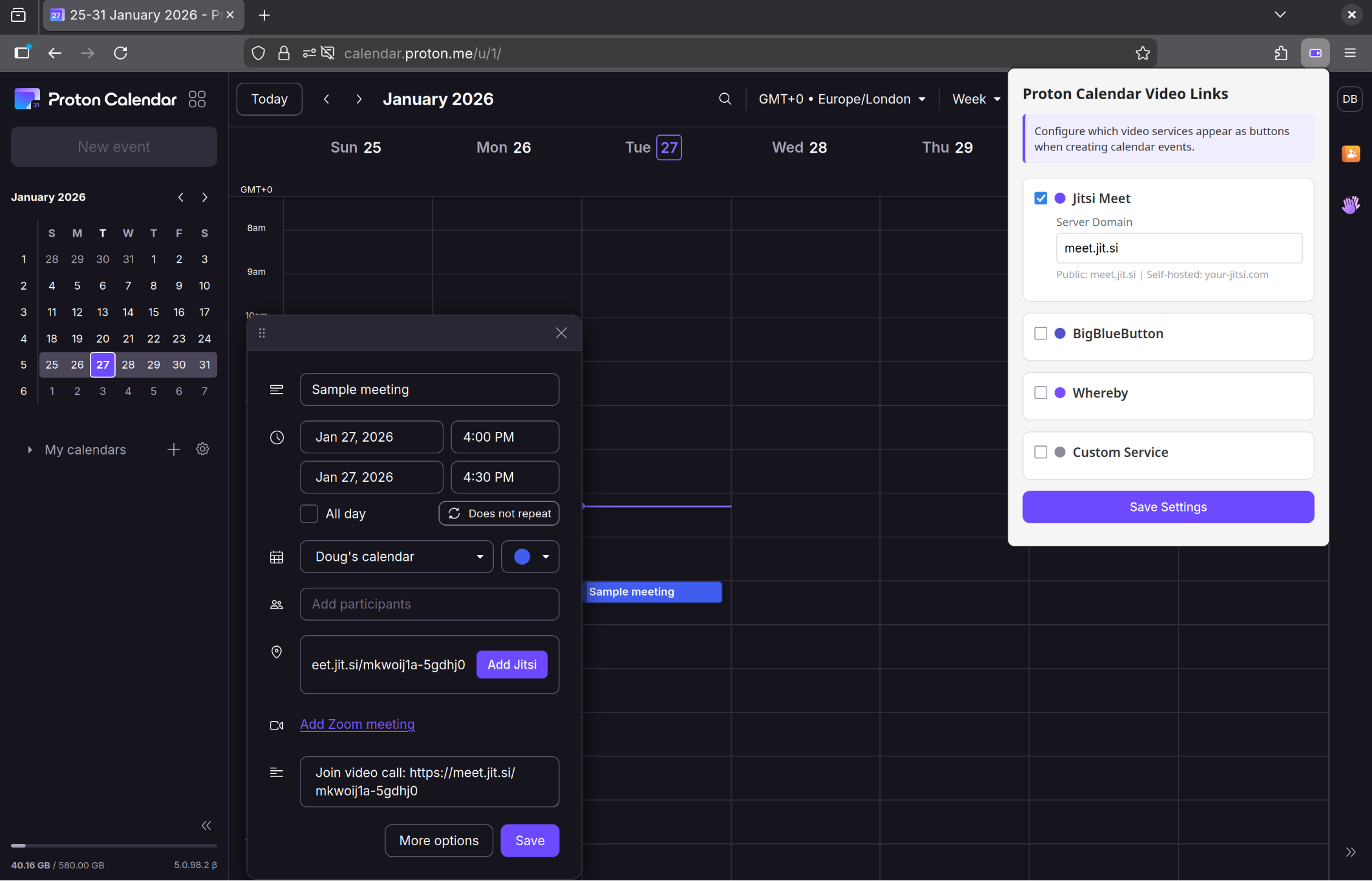

My main reason for moving from Google to Proton was to do with privacy and getting off US-based tech. There are trade-offs, however. Proton Calendar intentionally has no API, which means that, other than those which are supported natively by Proton, there is no one-click way to add links to video conferencing apps.

Rather than accept that limitation, I built a browser extension using Claude Code that adds video conferencing links (Jitsi, BigBlueButton, Whereby, or custom) directly into calendar events. It is open source and available on GitHub.

I think this illustrates something about extended minds: sometimes you have to build your own cognitive scaffolding. The act of building it – specifying requirements, writing a Product Requirements Document (PRD) for Claude, testing and iterating – is itself a form of thinking.

3. AI tools for planning and research

In addition to Claude, I use Perplexity and Lumo to help me plan, research, and (sometimes) structure blog posts, like this one. This is part of my extended cognition. I don't treat the first output as correct, but rather consider AI as a thought partner, deliberately asking for alternative framings and counter-arguments.

During my postgraduate study in Systems Thinking, I found it particularly helpful for coming up with other metaphors and similes to help me understand core concepts. So long as we're using these tools intentionally, they don't feel particularly harmful.

However, research on mitigating AI anchoring bias suggests we should employ the following strategies:

- Ask the AI to critique its own output

- Generate multiple versions before committing to one

- Treat the AI as a junior assistant: eager to help, but prone to errors and needing supervision

It's also worth explicitly asking, “under what conditions would this be wrong?” If that question sounds familiar, it should do; it's the same epistemic humility question from my first post in this series.

4. Paper-based prioritisation

Occasionally, when I've got a lot on and am feeling overwhelmed, I print out a paper-based daily planner that I created a few years ago to organise my work. It has sections for tasks and sub-tasks, prioritisation, time blocking, and emergent issues.

This is a form of low-tech cognitive scaffolding. The physical act of writing slows me down to be more intentional, and the fixed structure explicitly forces me to make choices about priorities.

Andy Clark and David Chalmers, the philosophers I mentioned at the top of this post, used the example of a man with Alzheimer's. He relied on a notebook to store information his brain can no longer hold. They argued that his notebook functioned as his memory in exactly the same way that your biological memory functions for you.

My grandmother did something similar when she almost entirely lost her short-term memory. Her kitchen was covered with notes to herself, which literally formed part of her thinking system.

While my daily planner isn't replacing a broken memory system, it is providing a prioritisation system. Left to my own devices, I can drift towards whatever seems urgent, so the planner helps me scaffold and make deliberate choices.

5. Sociocracy and consent-based decision making

So far, I have talked about individual tools. But minds extend into social systems too. At We Are Open Co-op (WAO), we use Sociocracy, which is built on consent-based decision-making. Consent is different from consensus and has many advantages.

One benefit is that it explicitly surfaces objections and treats them as information rather than obstruction. Instead of groupthink or the tyranny of structurelessness, you get a process where your only options aren't to simply “agree” or “disagree.”

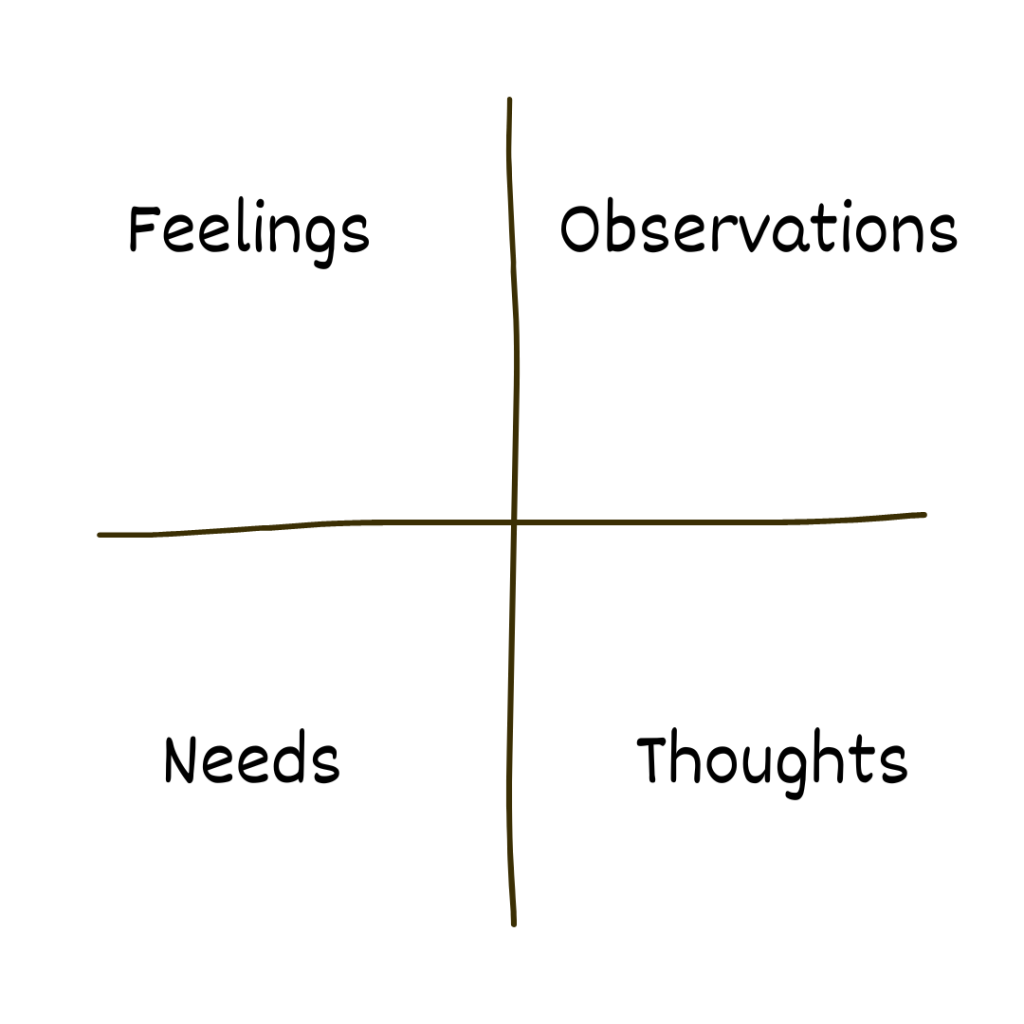

We also use check-ins which is something we've taken from Nonviolent Communication (NVC). Developed by Marshall Rosenberg, NVC is a framework that distinguishes between observations, feelings, needs, and requests. We operationalise it using FONT, and this has been transformative for me in dealing with conflicts, becoming more resilient, and bringing my full self to work.

What has this got to do with thinking systems and extended minds? NVC is cognitive scaffolding for emotion regulation and conflict. By providing a structure that reduces cognitive load in high-stakes conversations, it's easier to think clearly under pressure.

WAO, as the name suggests, works openly by default. We share documents, record decisions, and the reasons why we do things is made explicit. This isn't just transparency for the sake of it, but can be thought of as a way of extending our collective cognition.

The phrase “working openly” might sound like an overhead to actually getting things done. But, in practice, it's the opposite. It reduces the cognitive load of tracking who knows what, remembering why decisions were made, and reconstructing context when someone is away. For more on this, check out our free email-based course.

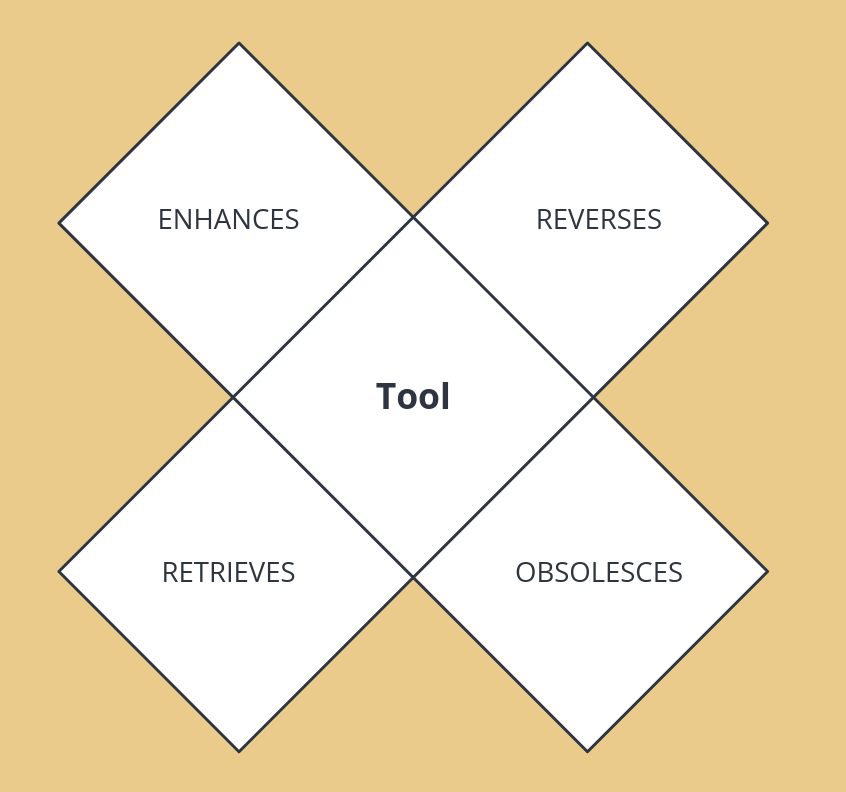

A McLuhan-style audit for your thinking system

Epistemic humility requires us to look at our whole thinking system, not just our intentions. Media theorist Marshall McLuhan suggested that every technology can be understood by asking four questions: what it enhances, what it makes obsolete, what it retrieves, and what it flips into when pushed to extremes.

We can adapt this “tetradic” approach as an audit for our own tools as a quick audit – for example, by using the following questions:

1. What does this tool enhance (and which biases does that make easier)?

Every tool makes some things easier and more obvious. So ask:

- Does this tool make certain signals louder (recency, notifications, “unread” counts) and others quieter?

- Does it encourage snap judgements and reinforce confirmation bias by surfacing what you already agree with?

- Does the way it presents information anchor you on the first result, suggestion, or message?

If a tool consistently enhances a known bias, you either need to change the tool or change how you use it.

2. What does this tool make obsolete (and what cognitive load does it add or remove)?

Tools replace practices, habits, and older tools. Sometimes that's helpful, but sometimes it quietly removes something you still required. It's worth asking, therefore:

- What did I stop doing when I started using this tool (paper notes, weekly reviews, face-to-face check-ins)?

- Does this tool reduce “extraneous” cognitive load (remembering dates, juggling context) or add to it (more inboxes, more formats)?

- Does it force me to translate between systems (calendar → task list → notes), or does it remove steps?

I've stopped experimenting with many tools which add complexity without a clear benefit. Otherwise, we're simply donating cognitive capacity we could use for actual thinking.

3. What older, helpful habit or capability does this tool retrieve (and does it support updating or lock me in)?

Some tools bring back older patterns in a new form: analogue-style planners, card-based note systems, shared decision logs. With these tools, we should ask:

- Does this tool retrieve a practice I had lost (daily reflection, spaced repetition, visual thinking)?

- Can I easily change my mind inside this tool (update beliefs, change status, rewrite decisions), or does it somehow “punish” revision?

- Can I see how my thinking has changed over time, or only the latest snapshot?

If a tool makes it hard to update your beliefs or records, then you could say it's working against epistemic humility.

4. If I push this tool to the extreme, what does it flip into?

McLuhan’s last question is about overheating – what a medium becomes when pushed too far. This can also apply to our tools, so we should ask ourselves:

- If I used this tool as much as possible, what would the failure mode be (burnout, compulsive checking, shallow work)?

- Does my use of this tool drift towards that extreme under stress (for example, living in my inbox or calendar)?

- Would turning this tool off for a week make my thinking better or worse?

It's not necessary to stop using a tool just because it has a failure mode. The point is to see it clearly and decide how far towards that edge you are willing to go.

Cognitive extension is a paradox

There's a deep tension when we use tools to extend our abilities. The more we externalise cognition into tools, the more dependent we become on those tools. If my thinking is genuinely extended into Anytype, Proton Calendar, AI tools, and my daily planner, what happens when those tools change or are unavailable?

Our identity is, at least in part, affected by our environment. Our thinking system is part of our extended cognition, so changes to the tools we use change our cognition, and therefore our identity. I felt this viscerally when Google announced Gemini integration into Gmail. Although I happily use AI for many things, the tools I had built my thinking around were being redesigned without my consent to serve someone else's priorities.

The answer wasn't a nihilistic shrug, but to choose tools over which I have more control, design systems that are portable, and maintain the ability to think without them – even if I rarely do. Scaffolding can be adaptive or maladaptive. Adaptive scaffolding temporarily supports thinking while you build new mental models, whereas maladaptive scaffolding creates dependency and prevents skill development.

So the distinction is whether the scaffold provided by the tools in your thinking system helps you become better at thinking or just makes thinking feel easier in the moment.

Final words

In my first post, I argued that shifting mental models is a prerequisite for systems change. I think the same applies to tools. We live in a polycrisis, but most of our tools were designed for world of isolated, linear problems. That means we drift back to short-term, reactive thinking because that is what the tools reward.

If you are trying to practise epistemic humility, but your tools punish revision and reward certainty, the tools will win. You will end up locked into an unproductive system which is atrophying your abilities – because updating your thinking system feels like more work than staying put.

The next post in this series will look at institutions and shared mental models. But before we get there, it is worth asking: what is your current thinking stack, and what is it optimised for?

This is the second post in a series on updating our mental models in a polycrisis. Read the first post on epistemic humility. The third post will look at institutions, inertia, and shared mental models at scale.