Helping strangers access the internet

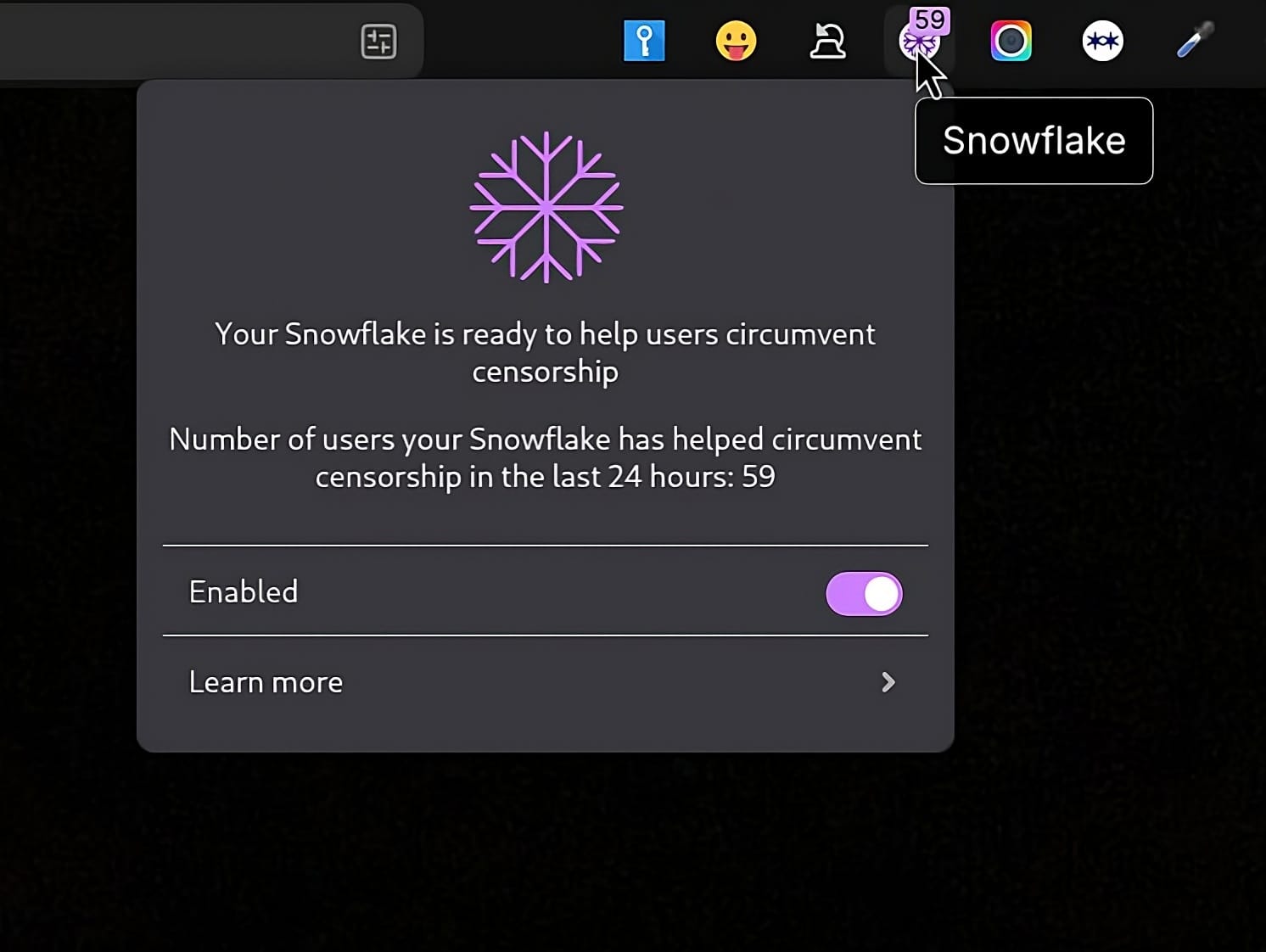

In the top corner of my Zen Browser window, I've got a little icon that looks like this:

What is it, and how it related to the fact that this blog is available via Tor on what some call the 'darknet'? 🤔

Introduction

Right now, somewhere in the world, you can bet a journalist is trying to report on corruption. A student is probably searching for information her government doesn't want her to find. An activist is attempting to organise resistance to authoritarian rule. And they might be using my bandwidth to do it.

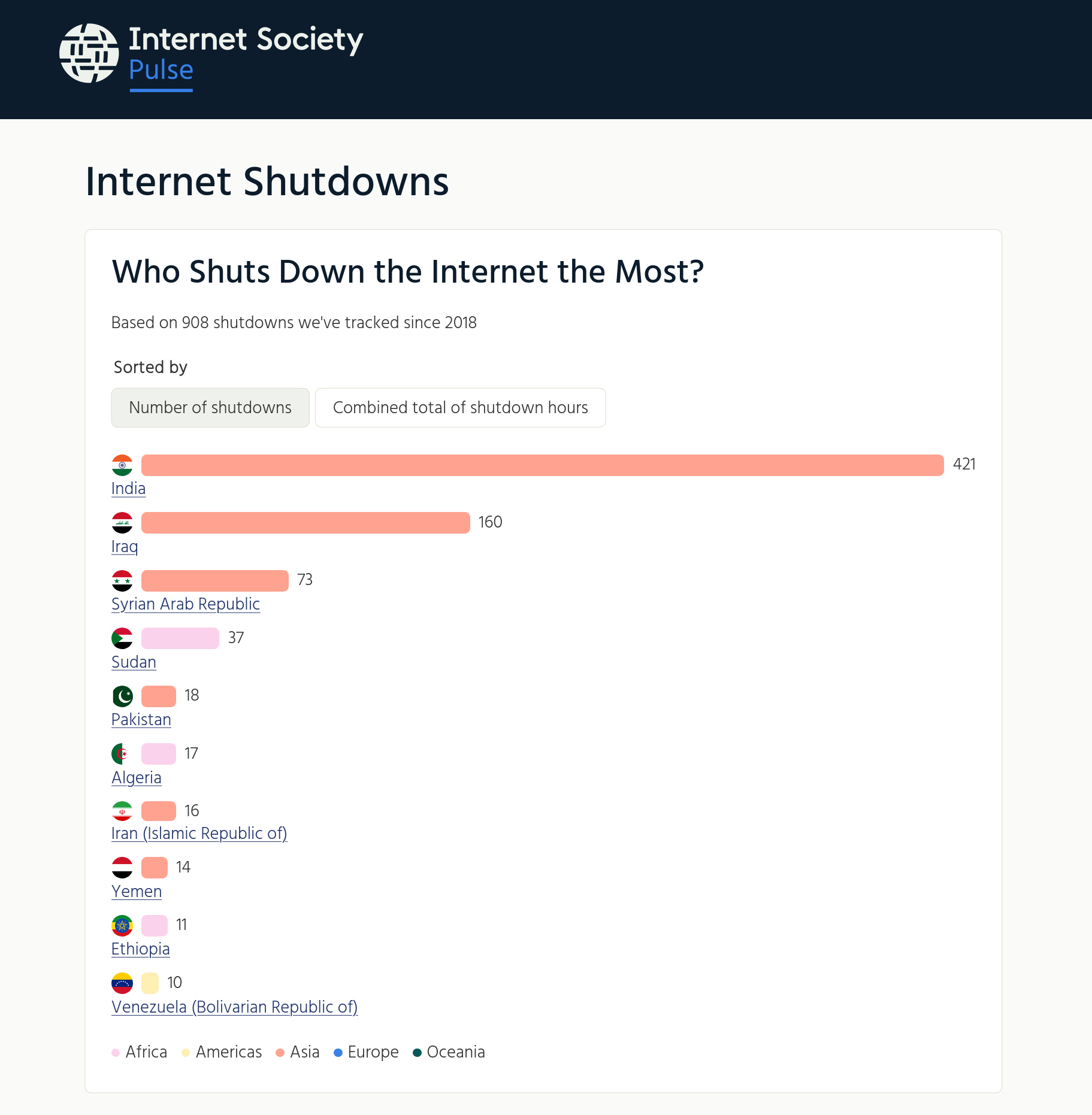

Sad to say, internet shutdowns are no longer rare exceptions. We don't yet have the full figures for last year, but in 2024 there were 296 shutdowns across 54 countries, which was a 35% increase compared to 2022. For many people living under censorship, circumvention tools like Tor make the difference between silence and having voice.

If you have a computer with an internet connection (likely if you're reading this!) then you can help. Just like voting, it's not about changing the world single-handedly, but rather by becoming a small node in a vast, distributed network that makes censorship much harder to enforce.

Internet shutdowns and human rights

The human cost is alarming. As I mentioned, we don't have the full figures yet for last year, but in the first part of 2025 alone, internet users lost 22,574 hours of access, and there are 10 shutdowns going on right now being tracked by the Internet Society. Behind those figures are journalists unable to publish, businesses unable to operate, and families unable to contact relatives.

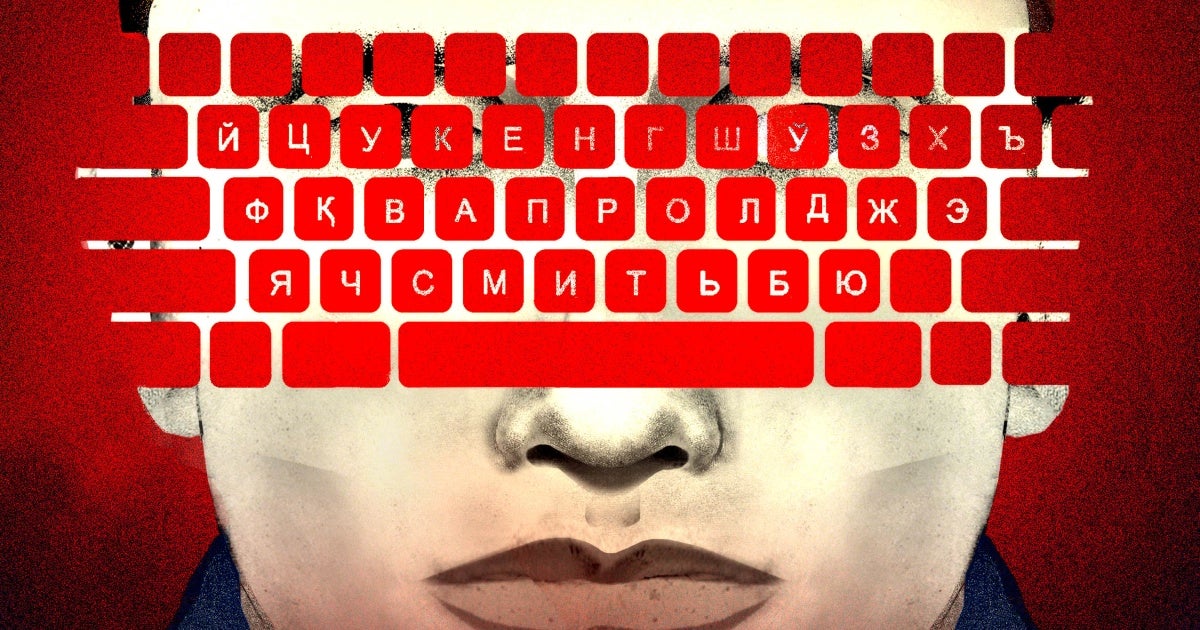

The use of VPNs is no longer enough. Shutdowns have become more sophisticated, wih governments no longer simply flipping switches, but employing censorship that's harder to detect and circumvent. Selective blocking targets specific platforms: Telegram is the most commonly blocked application, followed by X and various VoIP services. Partial restrictions are becoming the norm.

This is more of a human rights crisis than a technical problem to solve. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights protects privacy (Article 12) and the right to seek and receive information (Article 19). The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights extends these protections to the digital world. In 2021, the UN Human Rights Council adopted an explicit resolution condemning internet shutdowns as violations of freedom of expression.

Frank La Rue, the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression, didn't mince his words when he said that the internet is the "key means by which individuals can exercise their right to freedom of opinion and expression." Restrictions on internet access must be provided by law, must be necessary, and must be proportionate to a legitimate aim. Most shutdowns fail all three tests.

Refusing to take our infrastructure for granted

As we enter 2026, we live in an unstable world. A few days into the year, and we've already had Trump casually kidnap the President of another country. We assume our infrastructure and freedoms are permanent. They're not.

My work on systems thinking has taught me something important: centralised systems are fragile. A single point of failure can collapse the entire structure. But distributed systems with no single point of control are resilient. They can adapt. They survive.

The internet I use daily in the UK is the exception, not the rule. There are billions of people living under regimes that routinely shut down access, filter content, or monitor all traffic. Human Rights Watch's 2025 report makes sobering reading about state censorship and increasing isolation across dozens of countries. This is the current reality. This is the world we live in.

So the question isn't whether we should care. It's whether we're willing to step up and act when the tools to help are literally available to anyone with an internet connection. I mean, are you willing to install a browser extension? It doesn't sound hard, does it?

Becoming a 'snowflake'

Tor is a global network designed to prevent anyone from knowing where your internet traffic originates — or where it's going. It works by routing your connection through multiple servers run by volunteers. Each layer of encryption is removed only as your data passes through that server, hence the metaphor of an 'onion.'

As you can imagine, there are many places where governments block Tor directly, so this is where Snowflake comes in.

Snowflake uses a technology called WebRTC, the same technology that powers video calls on platforms like Google Meet or Jitsi. When you use Snowflake, your connection to the Tor network is disguised to look like a routine video or voice call. To censors monitoring network traffic, you appear to be doing something ordinary. You appear, to the network, to be having a conversation.

Instead of relying on a fixed set of servers that governments can identify and block, Snowflake works through a distributed network of “proxies” run by volunteers like you and me. At any given moment, approximately 140,000 unique IP addresses are hosting Snowflake proxies. These are ephemeral, constantly changing, moving targets that would be expensive and disruptive for governments to block.

You might be worried about helping people circumvent restrictions. That's understandable, but here's how it works:

- Someone in a censored region (let's call them a “client”) runs Tor Browser with Snowflake enabled.

- Their connection goes: client → a Snowflake proxy (possibly a volunteer like you or me)

- This then gives them access to a Tor bridge

- Which gets them onto the Tor network

- They reach their destination.

You, a proxy operator, never see the client's traffic. Your server doesn't know what websites they visit. Their browser traffic appears to exit from a Tor “exit node,” not from your IP address. You're simply the entry point, a bridge between someone trapped behind censorship and the global internet.

You may never heard of it before reading this post, but around 35,000 people use Snowflake daily, relying on volunteers like you and me. Collectively, they relay 29 terabytes of data daily. That's thousands of journalists, activists, students, and ordinary people accessing information their governments want to suppress.

It will only take you five minutes to help

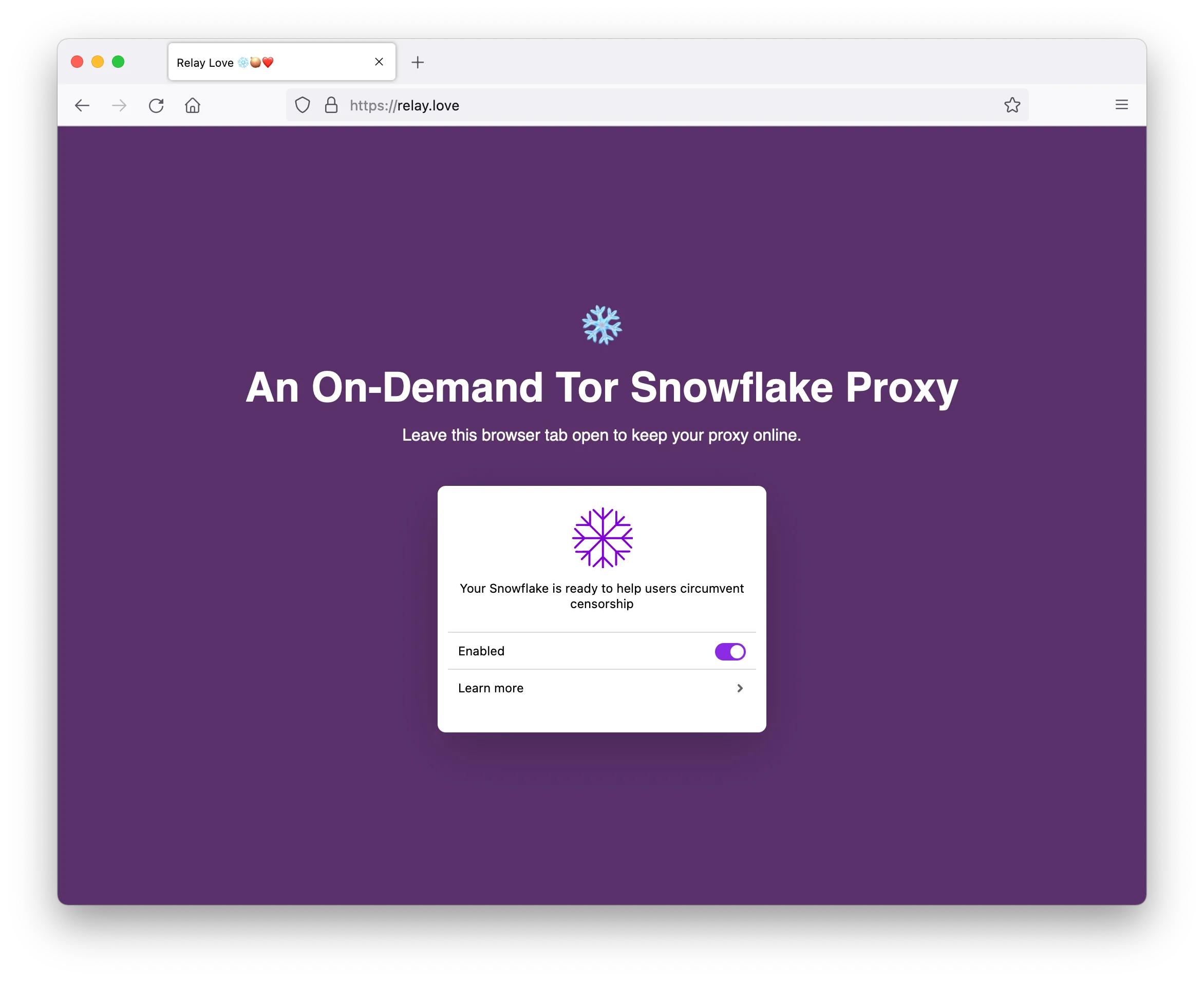

The simplest way to help is to install the Snowflake browser extension. All it takes is a few clicks.

Once you've got it installed, an icon appears in your browser toolbar. That icon shows your proxy status: green when active and helping people, purple when idle. The extension runs in the background, even when you're not actively browsing. You don't need to do anything. Users in censored countries who have Tor Browser installed can route their connection through your proxy.

From the extension, you can see statistics: how many users you've helped today, how much data has passed through your connection, and how long the extension has been active. In the time I've been writing this post, the counter in my Snowflake browser extension is up from 56 people helped in the last 24 hours to 60. That's not nothing. Bandwidth usage for the browser extension is typically minimal because you're only helping when Tor Browser users actively request it.

That's it! Install the extension and you're contributing to a global resistance against censorship.

If for any reason you want to stop, you can turn off or uninstall the extension at any time. There's no commitment required. But, before you do, just think about what happens if enough people in free countries maintain the extension: it's a network of hundreds of thousands of proxies that becomes progressively harder for authoritarian governments to disrupt.

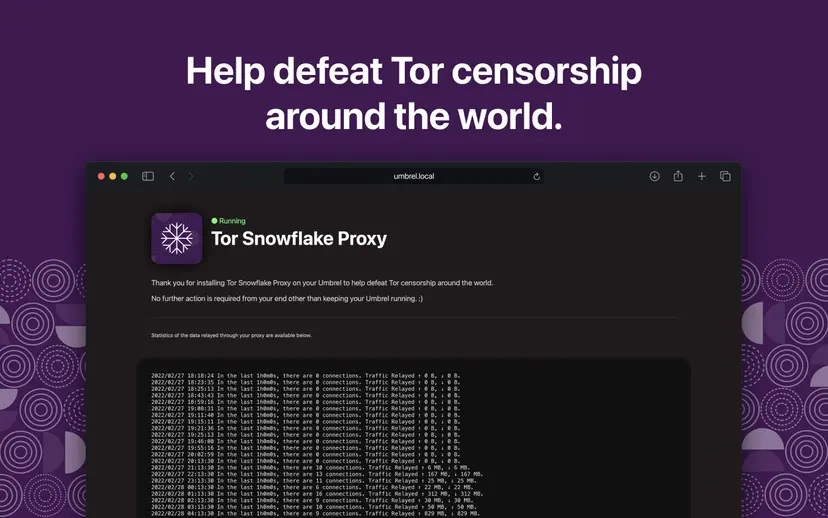

The more committed option

If, like me, you have a VPS (virtual private server) or a spare computer that runs continuously, you can run a more capable Snowflake proxy. This requires slightly more technical setup but provides constant, reliable availability. I'm running one alongside this blog, and if you've got a VPS or home server, you're already more than technically capable of running a Snowflake proxy.

The Tor Community provides detailed instructions on how to get started. The proxy requires no special firewall configuration. Snowflake uses NAT punching technology through WebRTC, so it punches through most firewalls without additional setup. The proxy listens on specific ports, but your VPS provider's default settings typically allow this.

While bandwidth is something to consider as a standalone proxy can handle far more traffic than a browser extension, I haven't had any issues so far. Real-world usage varies dramatically based on user demand. Some volunteers report 1 gigabyte per hour of traffic, whilst others see 7 terabytes per month on heavily-used proxies. The high end assumes unlimited capacity. Most proxies consume far less.

You can limit bandwidth using the capacity flag if you have concerns. I've added -capacity 10 to my startup command to cap simultaneous connections and prevent my server from being overwhelmed.

Interested? Great! Visit the Tor Community's Snowflake setup page for specific instructions to your setup.

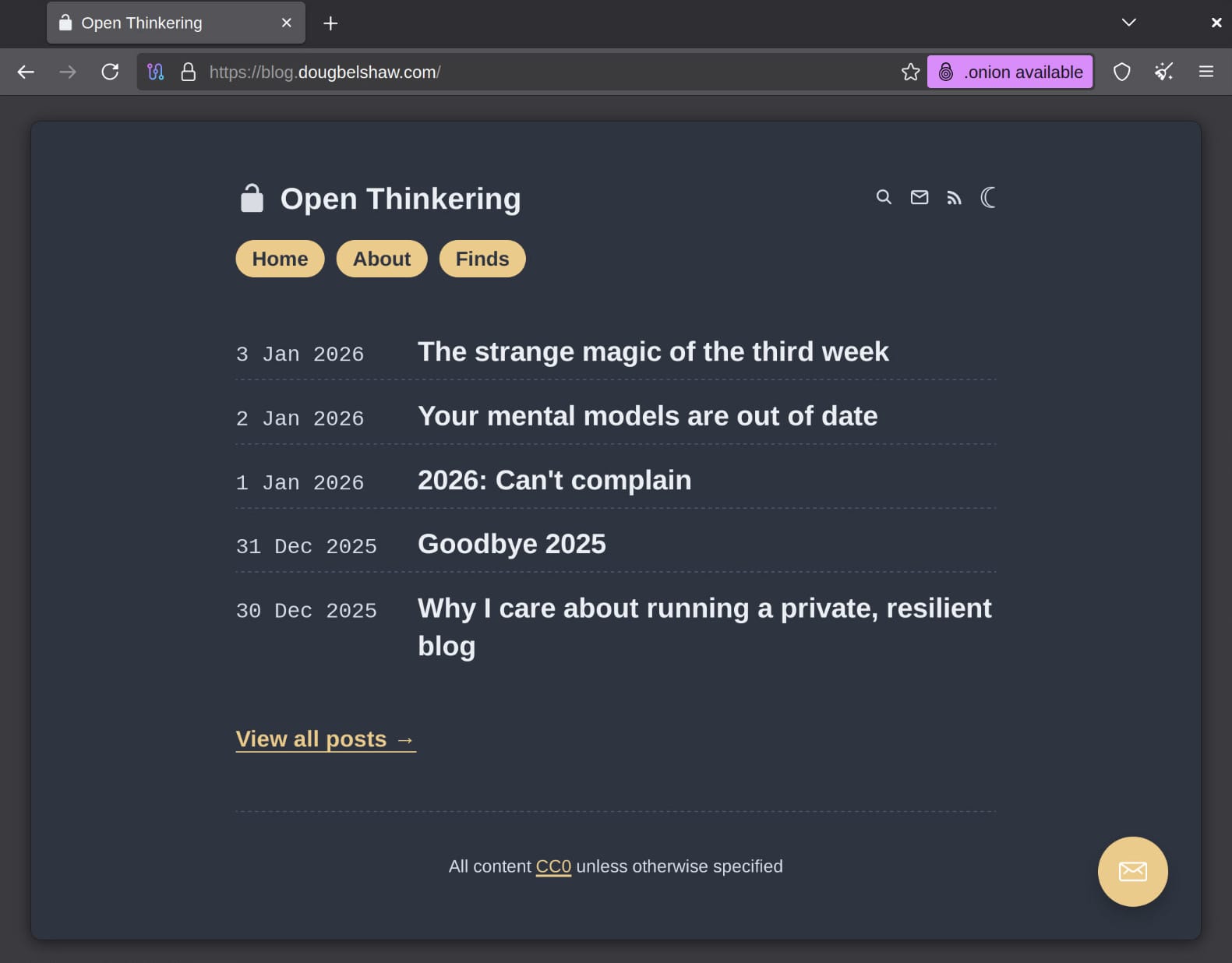

Going even deeper with .onion sites

So far, we've been talking about helping internet users access what's referred to as the “clearnet.” As I've explained, a Snowflake proxy helps users access the internet when it's blocked. But what about also making your own content available on the Tor network itself?

My blog is available via an .onion site at this link. Clicking on that in a regular browser will take you nowhere, but in the Tor browser, you'll access my content within Tor itself. That is to say, you will never exit the Tor network to the clearnet.

For users accessing from censored countries, this means the highest possible level of anonymity and protection. News organisations like the BBC run .onion mirrors of their content, ensuring that even if all clearnet access is blocked, people can still read their reporting. See this GitHub repository for an up-to-date list.

You don't need to be a news organisation to benefit from this. Bloggers like me, activists, educators, and anyone publishing content that's valuable to people in censored regions can (and perhaps should?) make their site available as an .onion mirror.

The basic process requires installing Tor on a server and configuring it to advertise your website as a hidden service. The technical steps are straightforward, and you can host multiple services on a single .onion address.

One important advantage of .onion sites is that they don't require SSL certificates. Tor itself provides the encryption. Your traffic is encrypted end-to-end within Tor, making additional HTTPS unnecessary.

For comprehensive instructions tailored to your specific setup, the Rocky Linux documentation provides excellent guidance, as does Comparitech's detailed guide to setting up hidden services. I literally just asked an LLM and it provided step-by-step instructions.

Supporting the Tor Project

It's worth noting that the Tor Project itself depends on funding from multiple sources. Transparency in funding helps ensure independence from any single organisation or government.

The Tor Project's budget remains modest relative to the impact and the adversaries trying to block its services. If you want to support the project directly, the Tor Project accepts donations at donate.torproject.org. They accept credit cards, cryptocurrencies, cheques, and bank transfers. Every contribution, no matter the size, helps fund development, security audits, and anti-censorship research.

Beyond donations, the Tor Project needs volunteers. If you can code, consider helping with development. If you speak multiple languages, try your hand at translation. If you're interested in policy work, legal expertise is always valuable and required. And if you host a website, making it available as an .onion mirror is a form of support that directly serves users.

What are you waiting for?

So there are three things you can do today. Right now, in fact!

- Install the Snowflake browser extension. It's quick, costs you nothing, and helps people across the internet in censored countries.

- Install a standalong Snowflake proxy, if you have a VPS or server running continuously. It will probably take you about 10 minutes.

- Make your content available as an .onion site, whether it's your blog, newsletter, or project documentation.

You have resources (bandwidth, server space, technical knowledge) that people in censored countries don't have. You have the ability to use those resources to help. In a year like this one, when internet freedom is under assault globally, I'm wondering whether that ability becomes a responsibility.

Right now, somewhere in the world, someone is trying to access information their government doesn't want them to find. Your contribution to the Snowflake network might help them do it.