Understanding yourself isn't enough

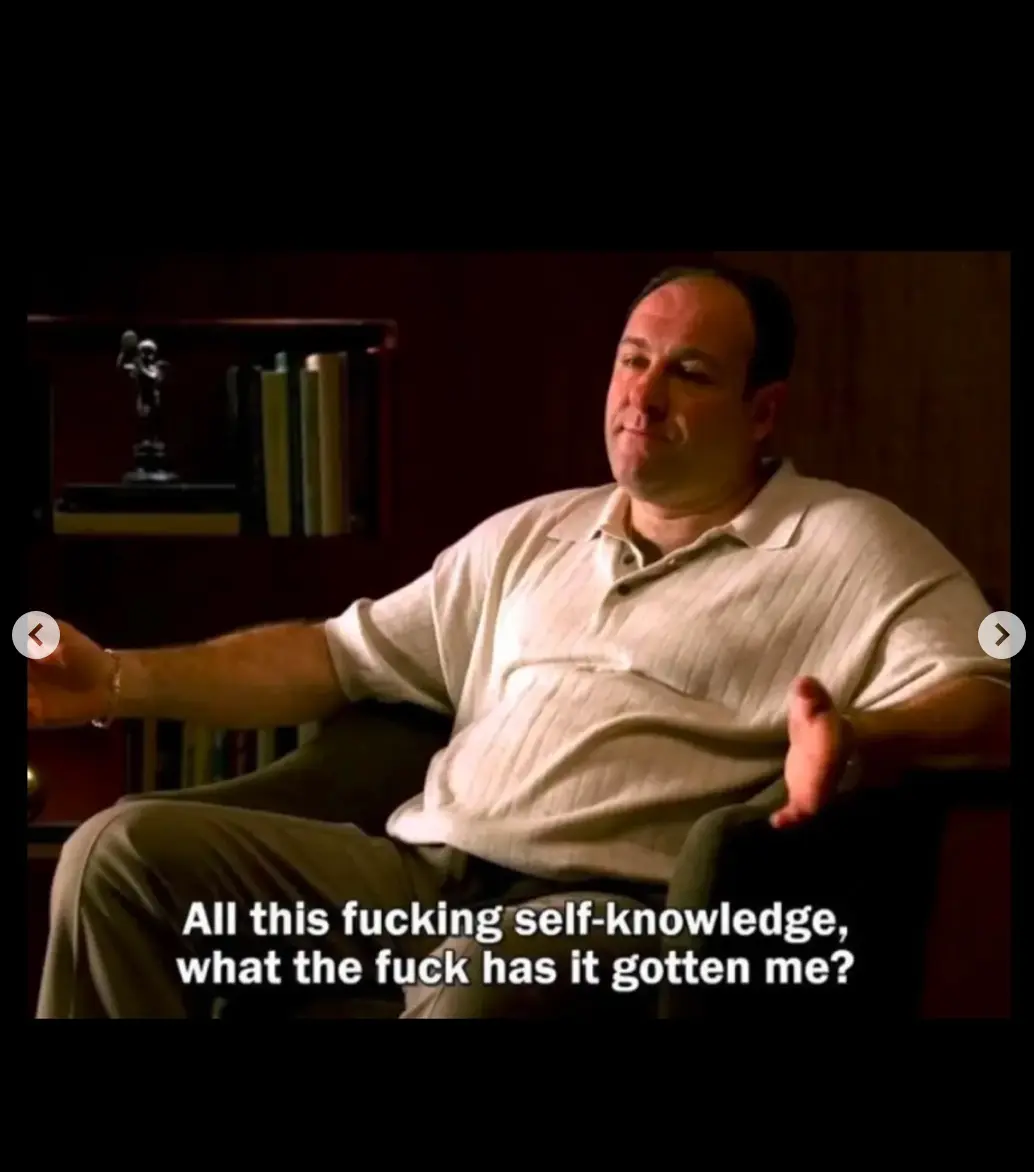

"All this fucking self-knowledge, what the fuck has it gotten me?"

Tony Soprano is uncomfortably close to the truth here. I've done the therapy. I've read the books. I have a degree in Philosophy and can introspect with enough precision to bore anyone who'll listen.

And I've understood, in theory, why I carry that quiet hum underneath everything; you know, the sense that I'm not quite good enough.

But understanding why you're stuck is not the same as being unstuck.

I hit a wall last year. It turns out there's a reason for that and I think I've found path forward that doesn't rely on yet more analysis.

The thinking person's trap

Here's what happens when you are a reflective person with formal training in philosophy: you become very (very) good at understanding yourself.

You can give a name to patterns of thought. You can identify the cultural forces that have forged your self-image. But none of it actually makes much difference in practice, because it's intellectualisation.

It's a defence mechanism in which reasoning acts as a buffer between you and the actual feeling. By providing a moments of insights the mind is stimulated, and even relieved, by the “aha” moments. But the body, including, of course, the nervous system? Not so much.

The research backs this up. Studies shows that mere insights alone don't produce lasting behaviour change. You can understand your problems (what is often called “trauma” with a great deal of clarity and yet still be trapped by it. It's a bit like being a passenger who knows the route but isn't driving.

A self-reinforcing system

If we think about ourselves through the lens of systems thinking, then it turns out that self-reflection can be a negative (i.e. reinforcing) feedback loop. For example, it can work like this:

- You feel inadequate.

- You analyse why – through philosophy, introspection, and/or therapy

- You get relief and a semblance of control

- This reinforces the pattern: more thinking must be able to solve this

- So you spend more time in your head, detached from lived experience

- The original feeling, meanwhile, remains untouched

The loop is closed in a way that optimises just for understanding rather than for change.

This is especially true if you're intelligent, articulate, or self-aware. The system actually works too well. Your insights generate dopamine and each realisation feels like progress.

Meanwhile, you're still sitting in the same chair, feeling the same thing, only now with a more sophisticated map of why you're trapped. Yay.

So how do we ACT?

If Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) – the type I've experienced before – is about changing what you think, then another framework changes your relationship to your thoughts altogether. It's called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and it works in a different way.

The main difference with ACT is that it treats your thoughts and feelings as noise, not problems to be solved or rewritten. What matters is where you place your attention and what you do next. It's a bit Buddhist in that regard.

ACT has several parts, but the two I want to mention here are cognitive defusion and self-as-context.

Cognitive defusion: thoughts are not reality

Defusion means “unhooking” from thoughts. You stop treating them as literal truths or commands. The thought I'm not good enough doesn't disappear but instead the idea is that you relate to it differently.

Again, in a way that seems very similar to Buddhism and various flavours of mindfulness, you notice the thought and name it: “I'm having the thought that I'm not good enough.”

It's a way of observing that the thought is just language, just noise, passing through awareness like a police siren you can hear from your window. The siren is real; the noise is real. But the chances are, it doesn't have to direct your next thought or action.

Over time, the thought loses its hold on you. That's not because you've convinced yourself it's false, per se, but because you've stepped back from the belief that you have to somehow “obey” it.

Self-as-context: your are the observer, not the observed

The second part of ACT feels less familiar but is potentially even more powerful. It's the idea that you are not the content of your thoughts and feelings, but merely the space in which they appear.

One way of understanding this is that our mind is the sky. Thoughts and feelings are the weather: sometimes sunshine, sometimes storms, or sometimes (like today) snow. The sky doesn't change, but the weather does.

This sounds abstract (and a bit “woo”). But it's surprisingly effective. There's a part of you that can observe the feeling of inadequacy without being inadequate. Not by denying the feeling or reframing it, but by shifting where you stand to be a more detached observer, a kind of witness to what's going on.

This isn't a new age thing as it's been researched in clinical trials. In fact, ACT has been shown increase what researchers call psychological flexibility.

Going even further

But even if you come out of the other side of CBT and ACT, these are only just tools to clear the decks so that you can do something even more important: live life according to what actually matters to you.

When we're in the doldrums we do, of course, want to feel better. But ultimately we're trying to live better.

What do you care about? Not what should you care about or what would impress people. What would make your life feel meaningful and vital? This is what I've been asking myself recently.

Once you know that, it's easier for behavioural change to become purposeful as you're not trying to fix yourself or think better thoughts. You're moving towards something you value.

And this is where I think it gets interesting: the "I'm not good enough” thought can still be there. But if you're moving towards someone or something you love, or think matters, the thought becomes irrelevant. It's just noise in the background.

To a great extent it's just another version of imposter syndrome – which can actually be developmentally beneficial

What I'm doing differently

So here's what I'm trying to do in 2026. Nothing particularly complicated or revolutionary, but instead some simple steps:

- Using "yes, and...” – Instead of thinking that I can't do something because I feel inadequate, I'm starting to say to myself, "yes, I feel inadequate, and I'm doing it anyway.”

- Providing proof through through action – Our nervous systems learn through experience rather than philosophical argument. So I'm trying to do things that go against my learned story of inadequacy and and perfectionist tendencies. Asking for help, being visibly wrong, and sending imperfect work. The brain, after all, rewires through repetition, and my nervous system will learn that the predicted catastrophes... rarely happen.

- Physics over philosophy – Although it absolutely can help to write feelings down, sometimes it feels like marinating in negativity. So I've committed to walk, go to the gym, or do something with my hands. Anything that requires attention in the present moment rather than trying to think my way out of the situation.

Back to Tony's question

"All this fucking self-knowledge, what the fuck has it gotten me?"

Well, the self-knowledge, the insight provided a map. It provided some clarity so that you're not flying blind any more. But it's true that the map is not the territory. And if you're like me, then you've been staring at the map for a long time.

So the next step isn't trying to achieve another revelation. It's movement. Not avoidance away from the feeling (that doesn't work), but movement alongside it.

Tony stayed stuck because he wanted the feeling to disappear before he changed anything. He wanted certainty before action. That's not how it works. The feeling doesn't go away first. You go ahead anyway, carrying it with you.

I'll let you know how I get on.